【ウェルビーイングの科学と政策】 Prof Lord Layard × Prof De Neve 対談

「ウェルビーイングの科学と政策」 Prof Lord Layard × Prof De Neve 対談

by Oxford Martin School

☑︎ 本対談の内容は、Oxford Martin Schoolが公開している動画を元に、ChatGPTおよびDeepLを併用して日本語訳を紹介しています。訳の正確性や完全性などを保証するものではありません。翻訳プロセスにおいて、意味の取り違えや誤解釈が生じる可能性があります。あらかじめ、ご了承ください。

この動画は、イギリス、オックスフォード大学にある研究機関、Oxford Martin School(オックスフォード・マーティン・スクール)の3人の教授の対談です。科学的な根拠に裏打ちされたお話しを通じ、とても哲学的で興味深い視点を提供しています。

ときおり日常生活で実感することができる深遠なテーマに触れ、言葉の奥深さに迫ります。知的好奇心をくすぐる内容でありながら、普段の生活においても確かに感じることができる事実があり、深い思索を促す一方で、楽しさも兼ね備えたお話です。

科学者のさまざまな視点から生まれる洞察や、深く考えさせられる言葉を通じ、また話者と聞き手の敬愛の姿勢も、私たちが得られる貴重な体験の一つです。新たな発見や気づきを、共に楽しんでまいりましょう。

目次

概要

幸福な社会と幸せな人生を生み出すのは何か?

ウェルビーイングの新しい学問領域は、この問いに答えるために、生活をより価値あるものにする要因に関する実証的な証拠を用いています。この学問領域は、将来の世代を含む私たち全員のウェルビーイングを最も重要視する能力を向上させ、私たちの意思決定を変革することを目指しています。

Wellbeing Science and Policy

『ウェルビーイング: 科学と政策』

Richard Layard(リチャード・レイヤード卿教授)

Jan-Emmanuel De Neve(ジャン=エマニュエル・ド・ネーヴェ教授)

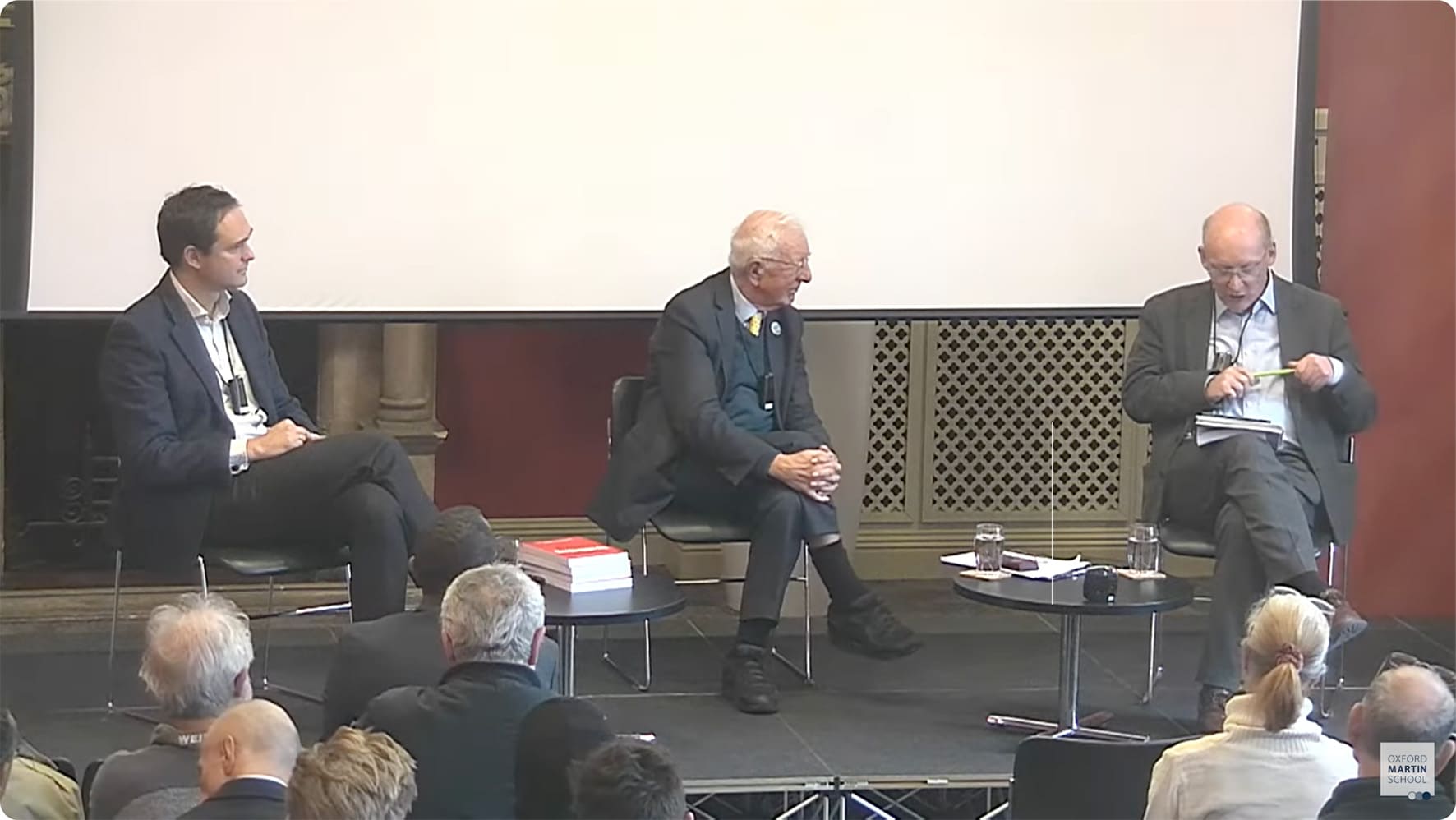

最近の共著『科学と政策に焦点を当てたウェルビーイング』という本の著者であるリチャード・レイヤード卿教授とジャン=エマニュエル・ド・ネーヴェ教授が、Oxford Martin Schoolのディレクターであるチャールズ・ゴドフレイ(Charles Godfray)教授と一緒に、ウェルビーイングの測定方法、その原因、および改善方法について議論します。

1-1. 対談の流れ(チャールズ・ゴドフレイ教授から)

チャールズ・ゴドフレイ教授:

こんにちは、皆さん。ここに、たくさんの方がいらっしゃってくださり嬉しいです。私の名前はチャールズ・ゴドフリー。オックスフォード・マーティン・スクールのディレクターです。今日は、リチャード・レイヤード卿とジャン・エマニュエル・ド・ネーヴェに、ウェルビーイングの科学と政策についてお話いただきます。簡単に2人の講演者を紹介し、それからこの新しい本について話し合っていただきます。

Wellbeing Science and Policy

『ウェルビーイング: 科学と政策』

Richard Layard(リチャード・レイヤード卿教授)

Jan-Emmanuel De Neve(ジャン=エマニュエル・ド・ネーヴェ教授)

この本は、ウェルビーイングの科学を非常に分かりやすくまとめたもので、強くお勧めします。その後、私たち3人で会話をし、質問の時間を十分に確保し、1時半には終了します。

1-2. 講演者紹介

リチャード・レイヤード卿教授:

リチャード・レイヤード卿は、ロンドン大学経済学部(London School of Economics: LSE)に所属する労働経済学者であり、1990年に共同創設された経済パフォーマンスセンターのプログラムディレクターを務めています。リチャードは数十年にわたり公共政策に影響力を持っており、特にブレア・ブラウン政権時代にその影響力を発揮しました。彼は英国アカデミーのメンバーとして1990年に男爵として叙せられるなど、数々の賞を受賞しています。

出典: Wikipedia / Lord Layard in 2006

ジャン・エマニュエル教授:

ジャン・エマニュエル博士はベルギー出身で、ハーバード大学とLSEに通いました。

出典: Wikipedia / Jan-Emmanuel_De_Neve

リチャードと共に世界幸福度報告書などの取り組みや、ワールド・ウェルビーイング・ムーブメント(世界ウェルビーイング運動)の共同創設者でもあります。また、彼はベルギー政府とも協力し、政策に深く関わっています。それではリチャード、上がっていただけますか?ありがとうございます。

2. リチャード・レイヤード卿教授から

さて、来ていただいた皆さん、ありがとうございます。こうしてこちらにいることは、私たちのウェルビーイングにとっても素晴らしいことです。満席です。何人かの同僚が入場できなかったようで、それは良いことです。それでは、私たちの本の最初のページから始めたいと思います。

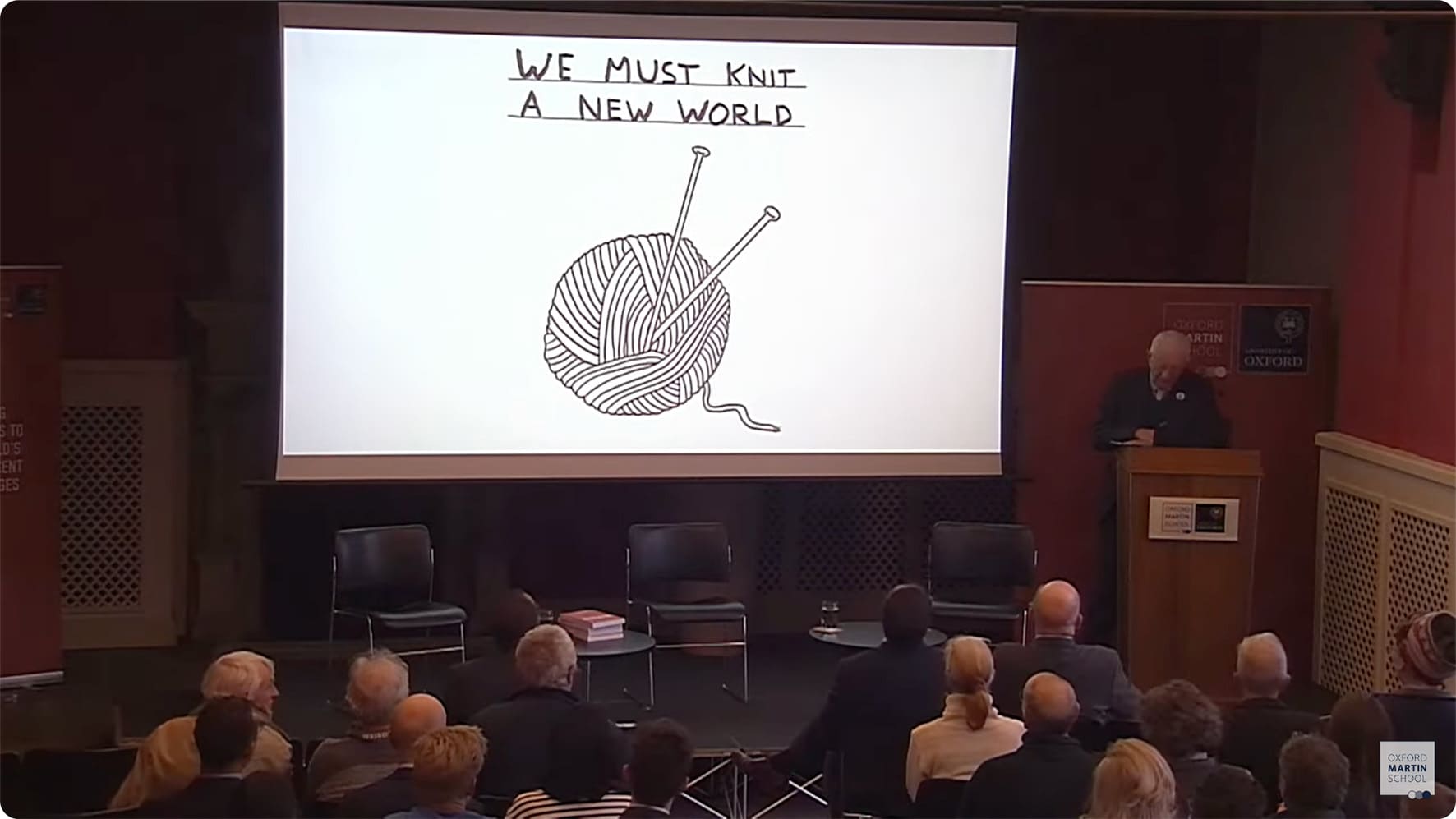

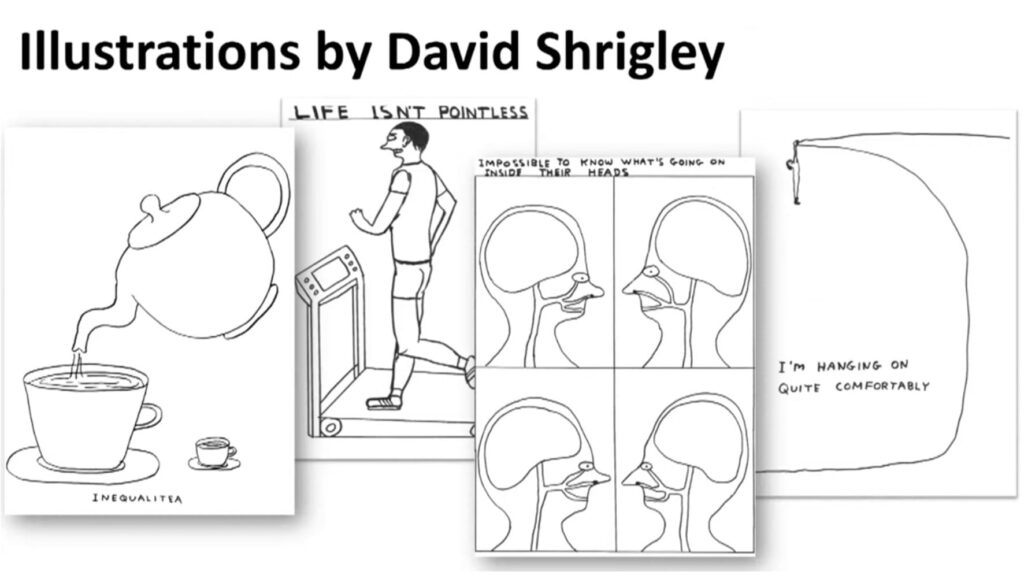

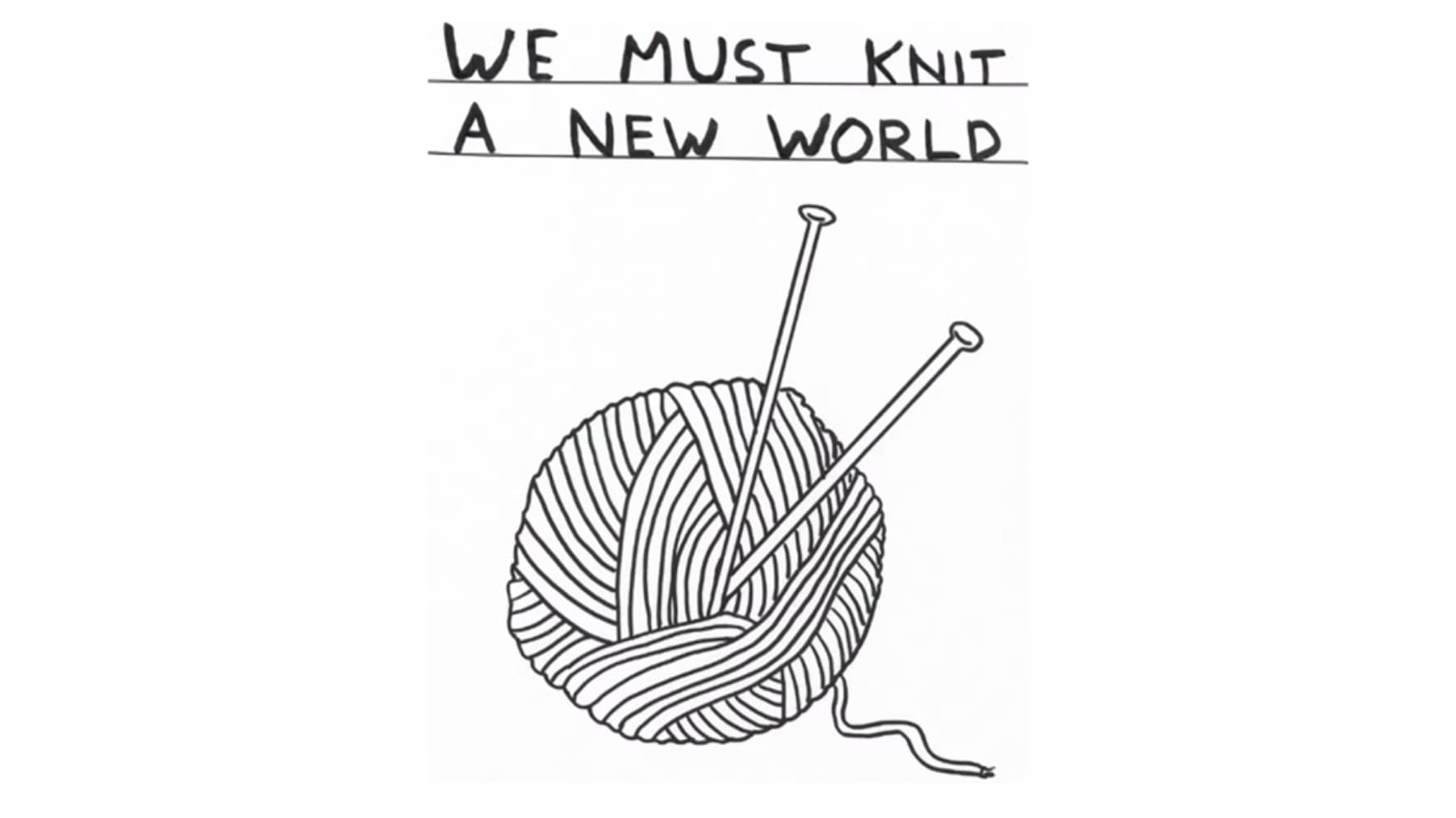

これは、一流のデザイナーであるデイビット・シュリグリー(David Shrigley)氏による18点の挿絵の一つです。それは、人々がより高いウェルビーイングを経験する、新しい世界の必要性を指摘しています。

我々がそれを目標としない限り、我々はそれに到達しないでしょう。

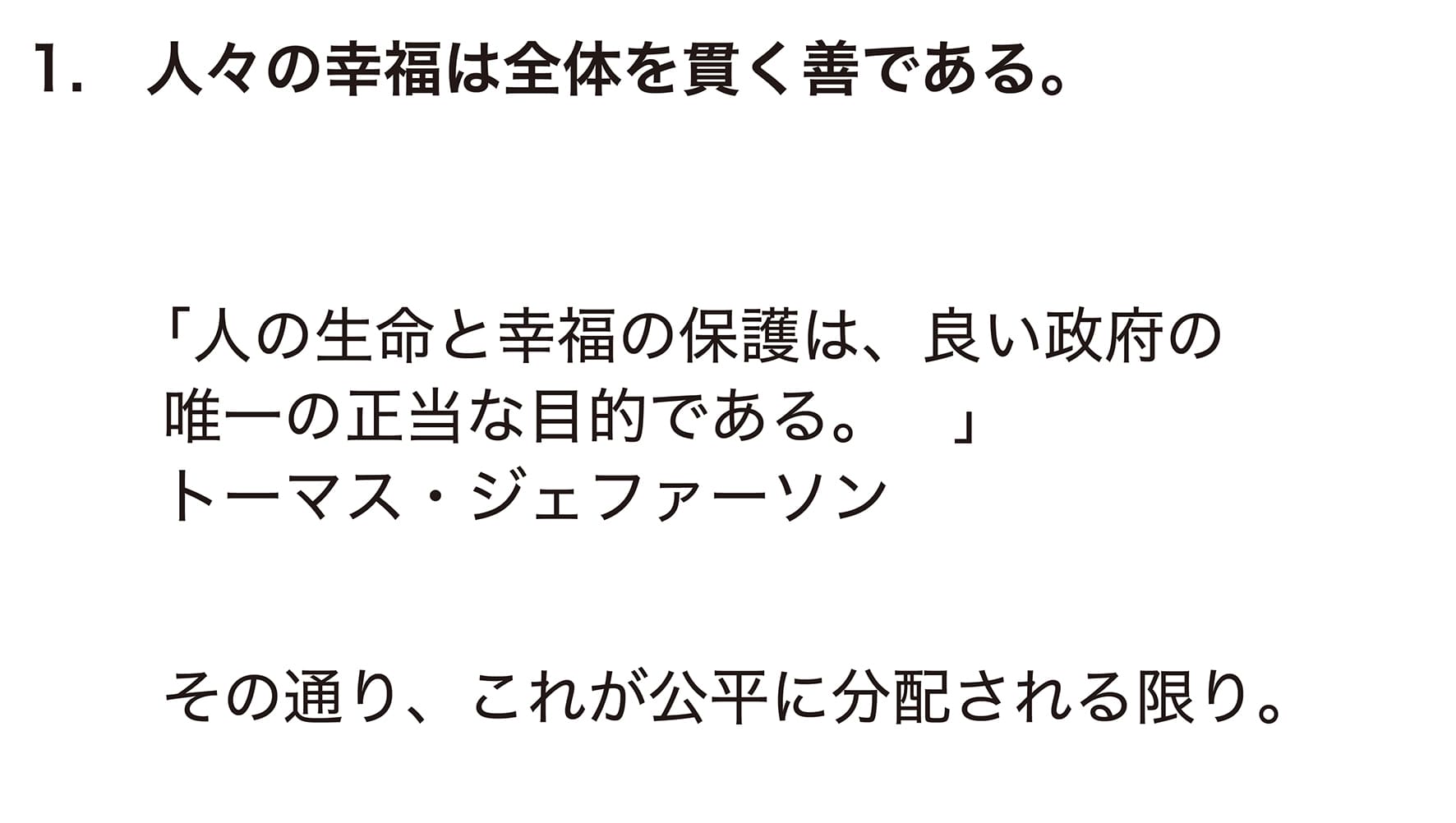

最初に伝えたいことは、我々はそれが目的であることを受け入れなければならない、ということです。最初のステップは4つのポイントを言いたいのですが、1つ目は目的が何かについて合意する必要がある、ということです。そうでなければ、我々はそこに到達できません。我々は人々のウェルビーイングが最も重要な目標だということに合意しなければなりません。

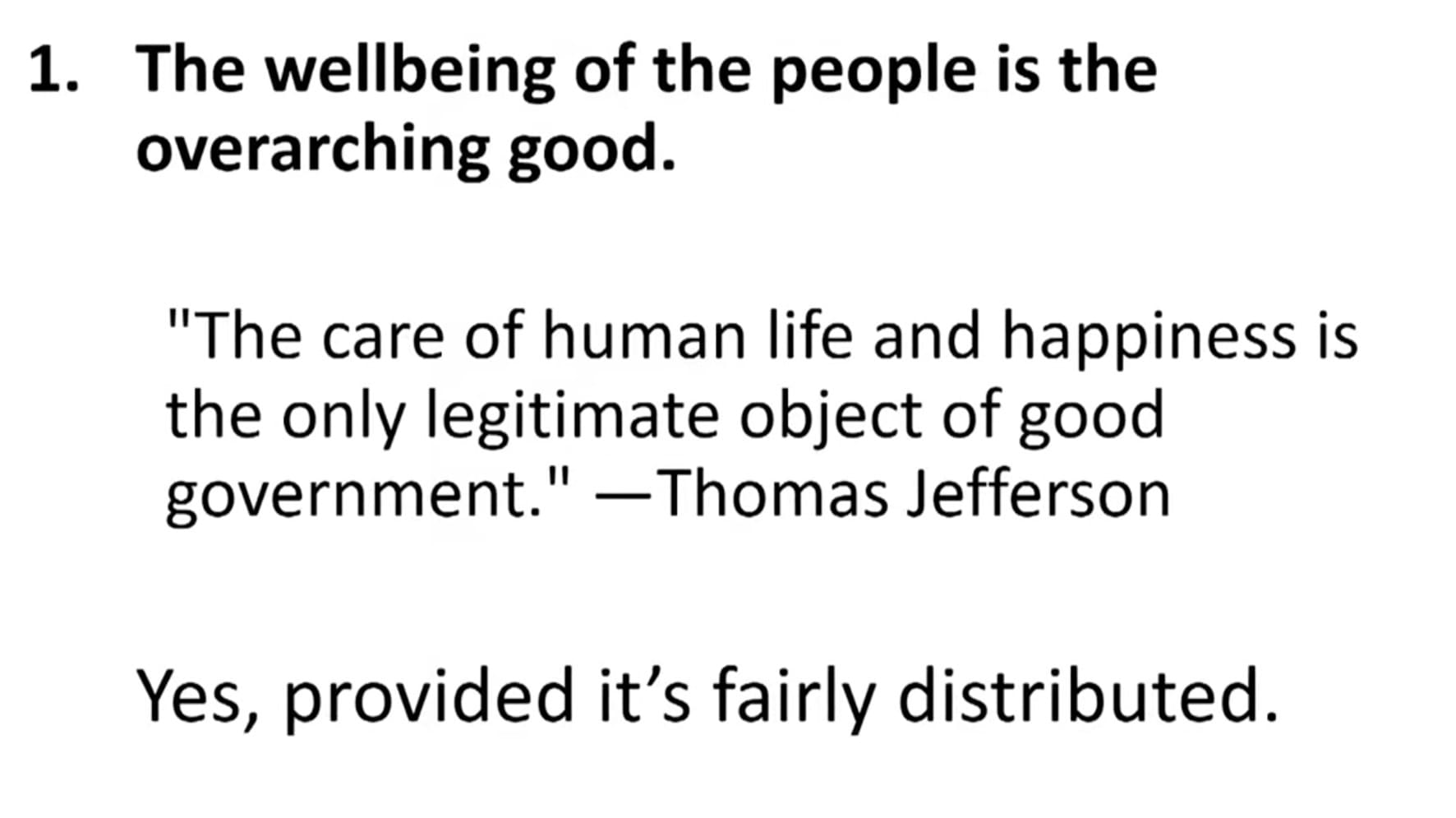

私は、トーマス・ジェファーソンが言った、「人間の生命の管理と幸福こそが、善良な政府の唯一の正当な目的である」という非常に強力な主張が好きです。政府は人々のウェルビーイングを向上させ、彼らの生活の質を向上させるために存在しています。

もう一つ重要な点は、幸福を公正に分配したいということです。現代の功利主義者は、ウェルビーイングを全体的な目標として分配に関心を持ち、ウェルビーイングが低い人々をできるだけ少なくし、悲惨な状況の経験に配慮しています。

功利主義とは:

原則は、「最大多数の最大幸福」または「最大多数の最小不幸」を追求することで、人々の幸福や快楽を最大化し、苦痛や不幸を最小限にすることを目指します。行動が幸福を増やし、苦痛を減らすならば、それは善であると考えます。逆に、幸福を減らし、苦痛を増やすような結果をもたらすならば、それは悪いと見なされます。

したがって、私たちが提案する理論は、政府は人々がより幸福になれるような条件を作り出す必要がある、ということです。特に、苦しんでいるであろう人々のために。

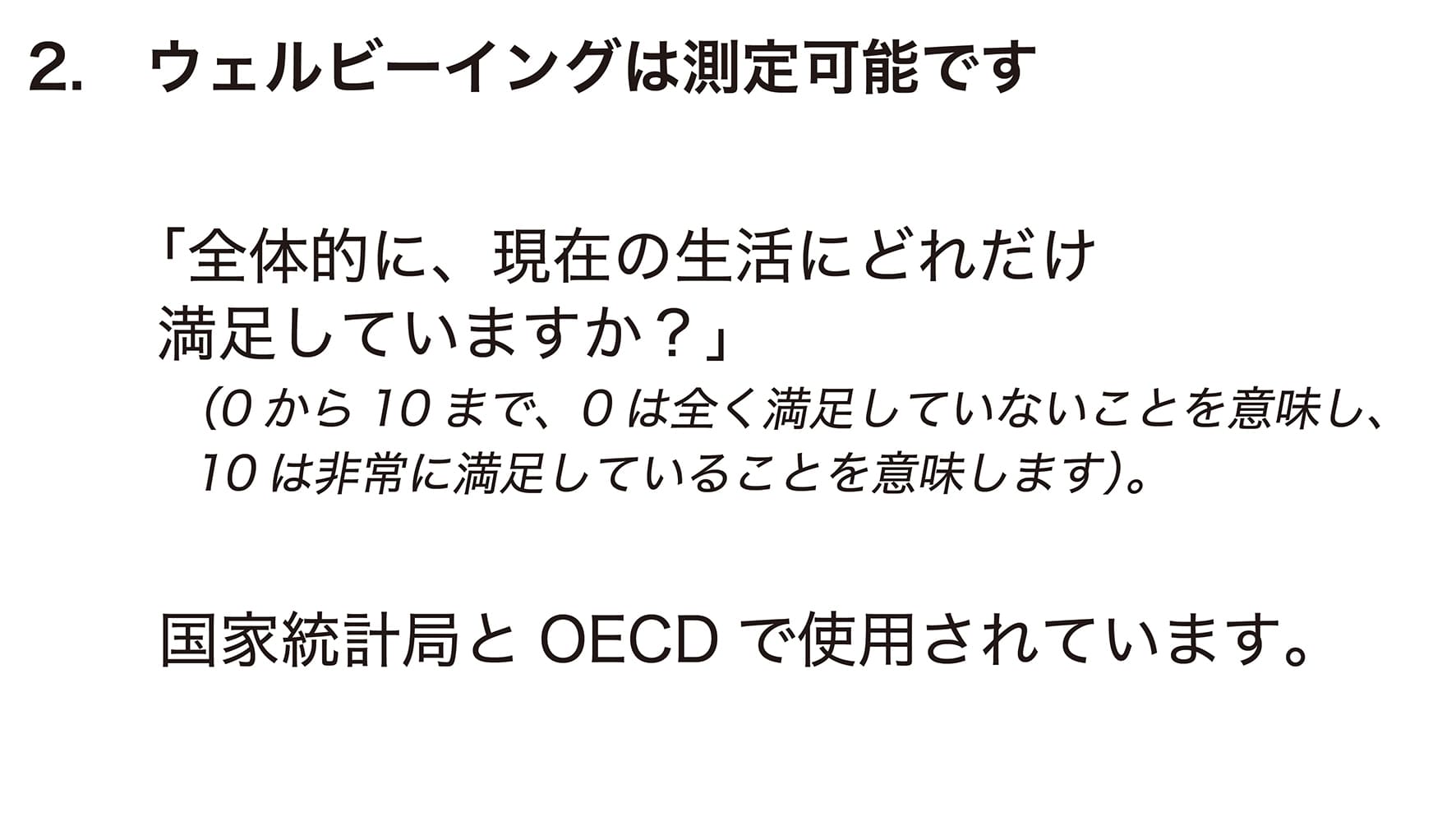

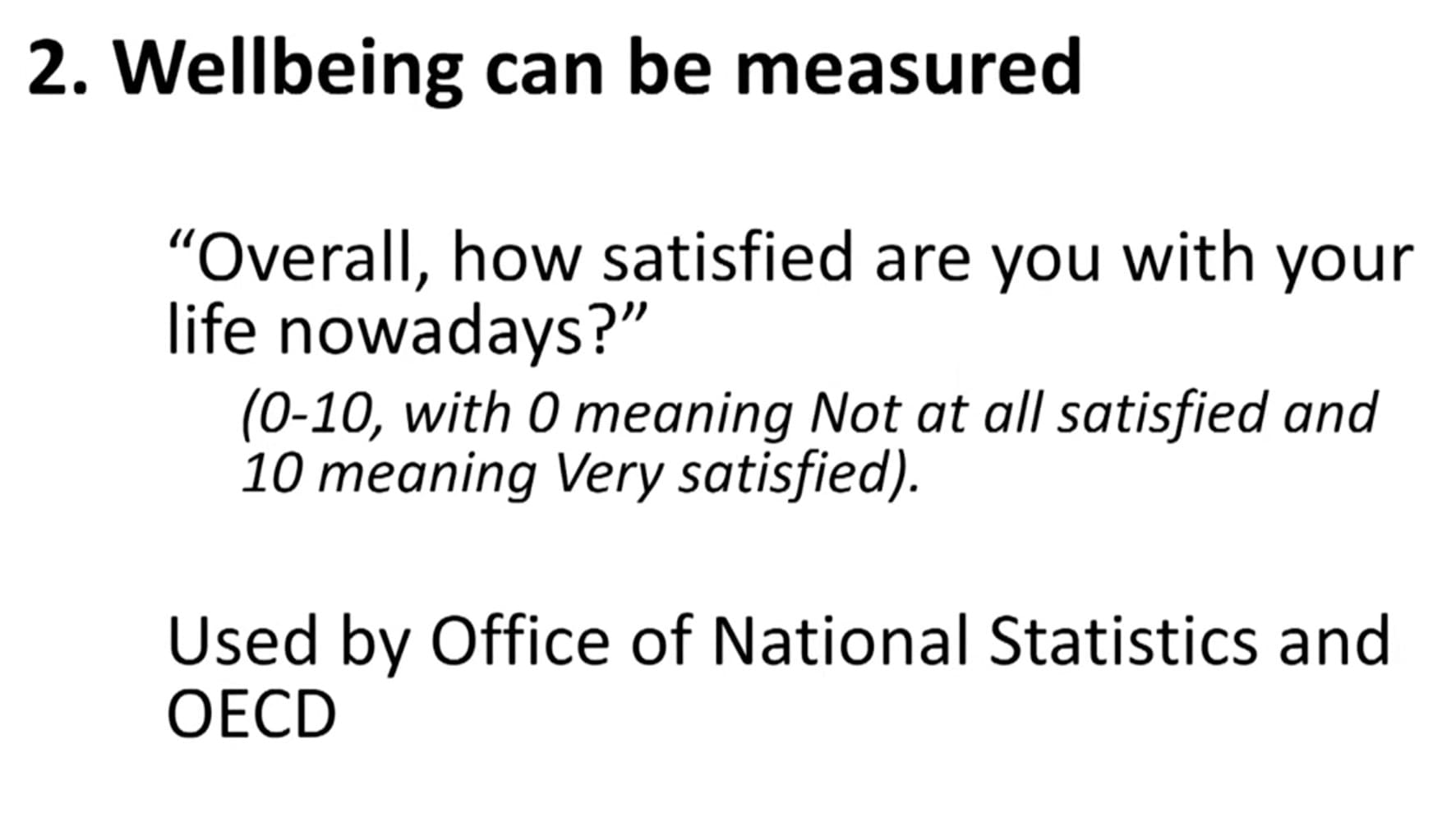

それでは、いくつかの経験の事例に移りましょう。誰が苦しんでいるのか、そして世界中でウェルビーイングが大きく広がる原因をどのように特定するか。これが、2つ目のポイントです。これは、計測が必要です。我々はウェルビーイングを計測できます。これは、過去40年間の革命でした。簡単に尋ねるだけで分かります。

この質問は、私たちのほとんどが好意的に受け入れる質問です。「全体的に、あなたは現在の生活にどのくらい満足していますか?」0はまったくそうでなく、10は非常にそうであることを意味します。

これは、政府統計局の調査で毎年使用される質問です。これが、イギリスの国家統計です。これは現在、OECDによって全ての加盟国に推奨されています。これには多くのメリットがあり、シンプルで理解しやすく、一部の場所で一般的に行われている方法よりも優れています。多くの質問を用意し、いくつかの価値を適用して指標を作成します。これは、研究者が価値を適用させるよりも民主的でもあり、重要なのはその人自身にとって価値があるかどうか、そしてそれに対してどのように感じるか、という点です。

この質問には、強力な情報が含まれていることはわかっています。それは、あなたがどれだけ長生きするかの非常に良い予測であり、医学的な診断と同じくらいです。それは、仕事やパートナーをやめるかどうかの良い予測でもあります。これについては、なぜ政策立案者がそれを特に重く受け取るべきかをジャンが説明します。

それでは、この質問が明らかにする人類の状態についていくつかの基本的な事実を見てみましょう。

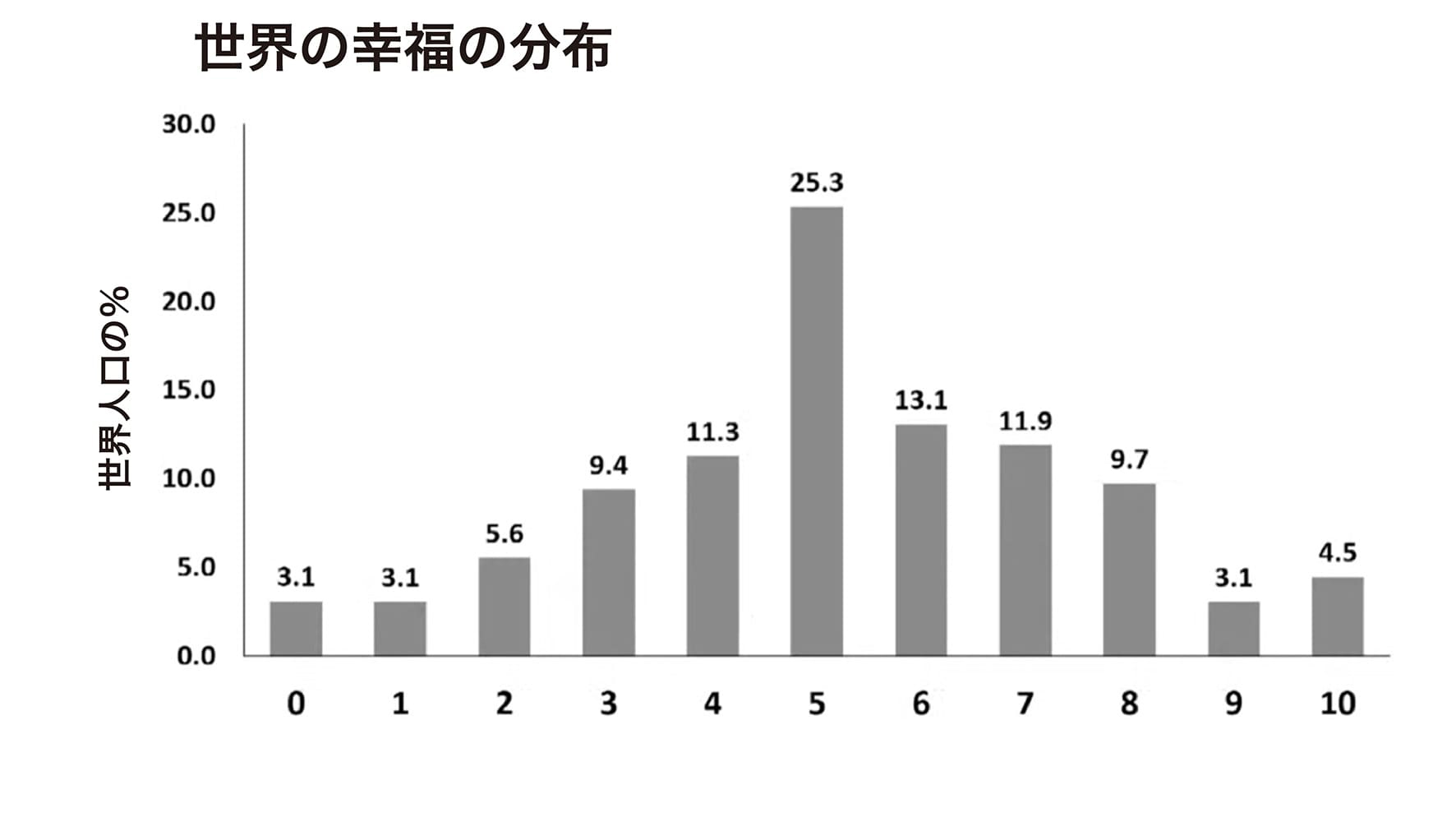

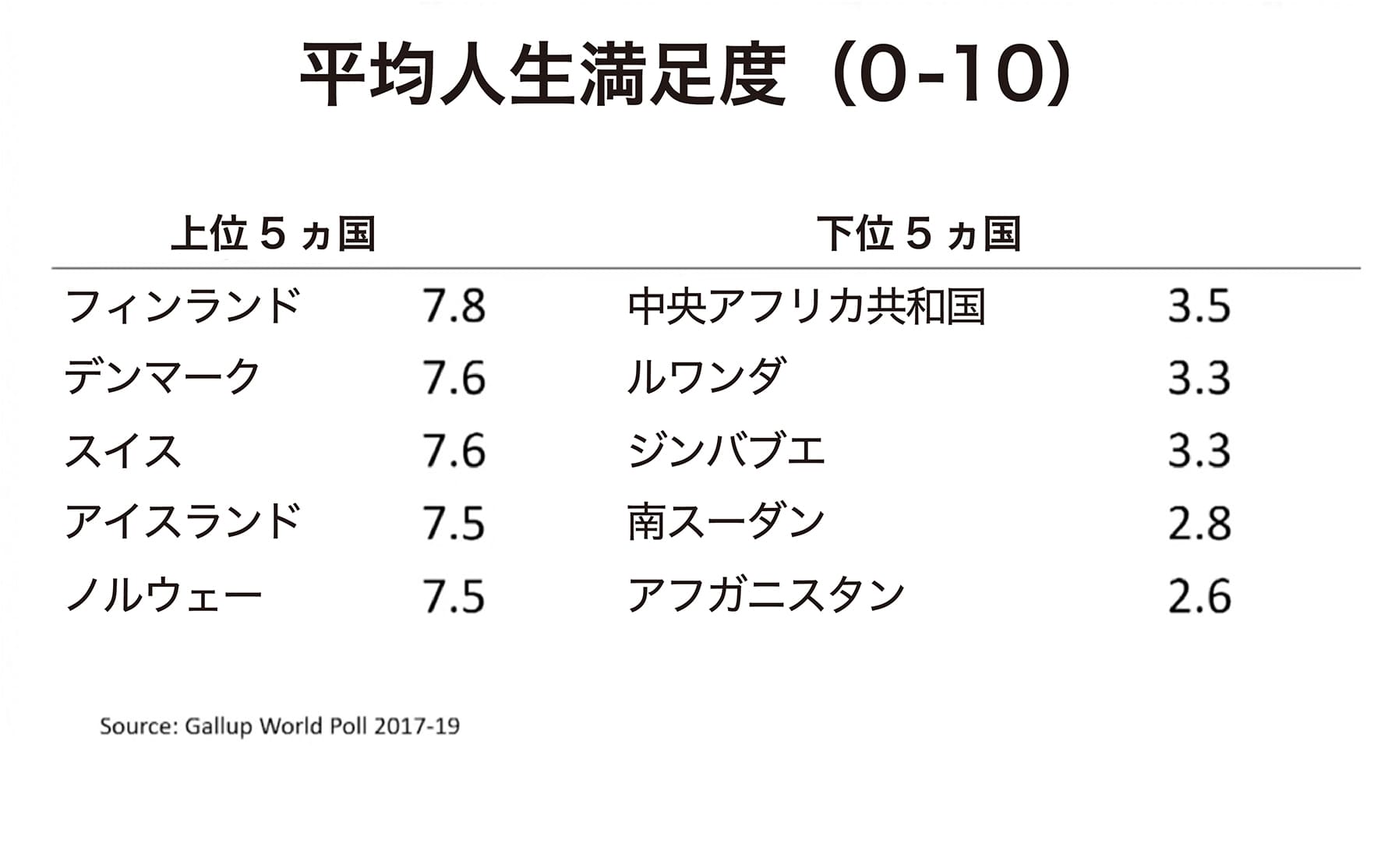

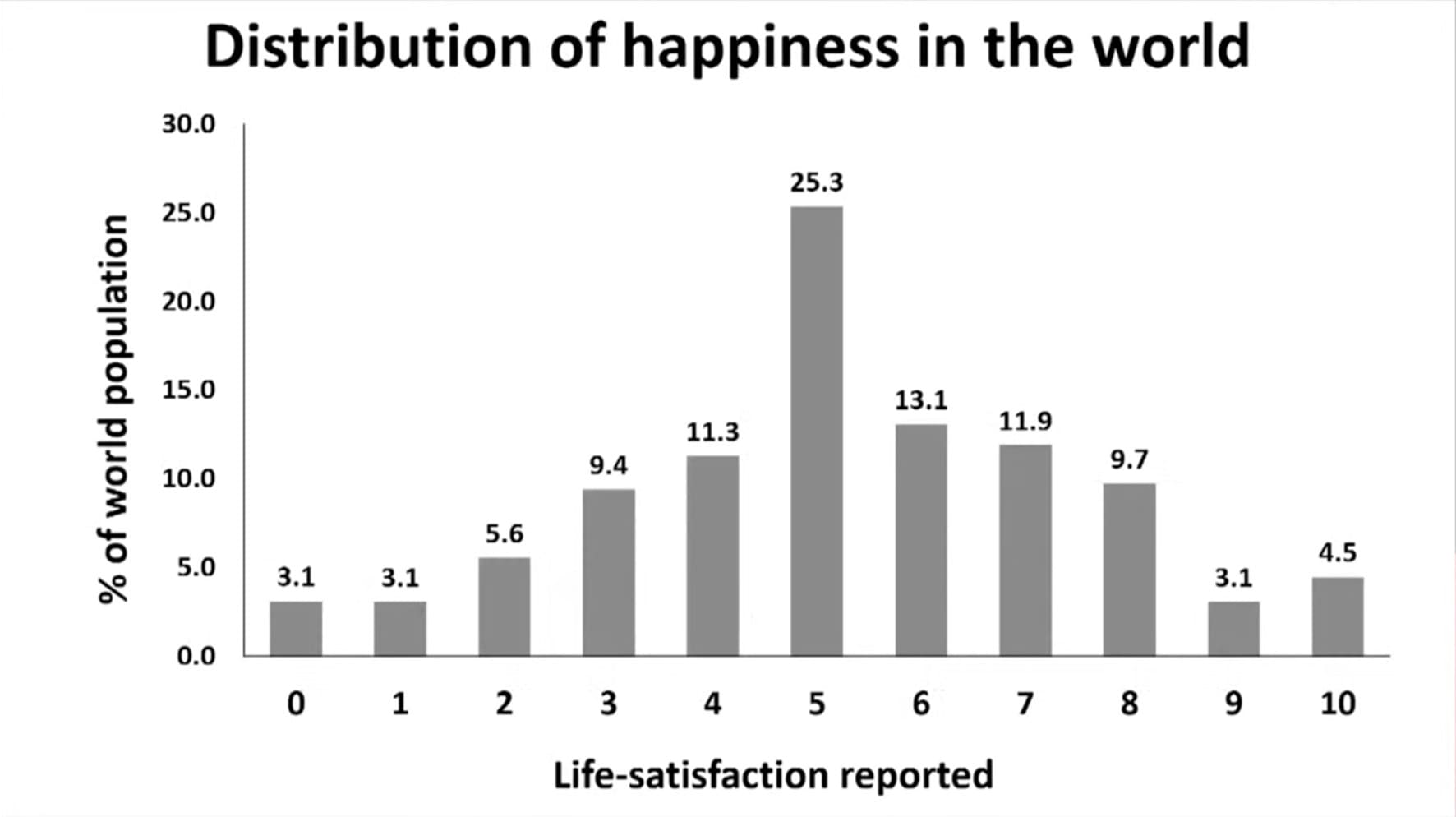

マーティン学派が焦点を当てているのは人間の状態だと私は知っていますが、これが世界のウェルビーイングの分布です。非常に不平等であることがわかります。5分の1が3以下で、6分の1が8以上です。もちろん、そのばらつきは、国々の間の差異と、国内の差異からも来ています。その順序で見てみましょう。

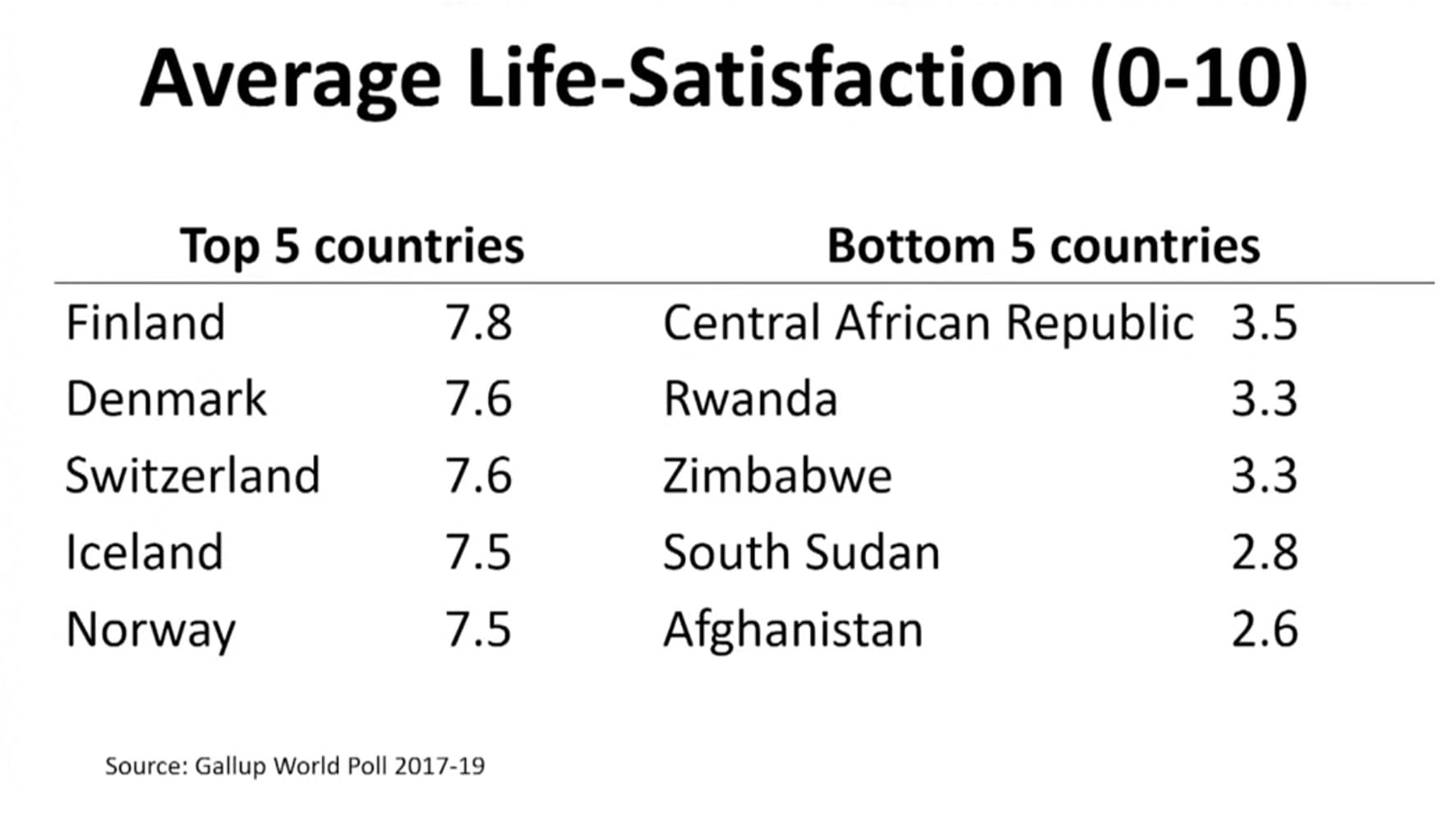

上位の国々は通常、北欧諸国の傾向があります。彼らは平和的で平等主義の傾向があり、下位の国々は内戦や抑圧に苦しむ国が多いです。しかし、もちろん国と国の違いを説明する他の要因もあります。所得だけでなく、健康、自由、社会的サポート、利他主義、信頼など。実際、有名な財布落としの実験では、北欧諸国で落とされた財布の80%が返却されましたが、英国と米国では半分以下で、中国では20%未満でした。

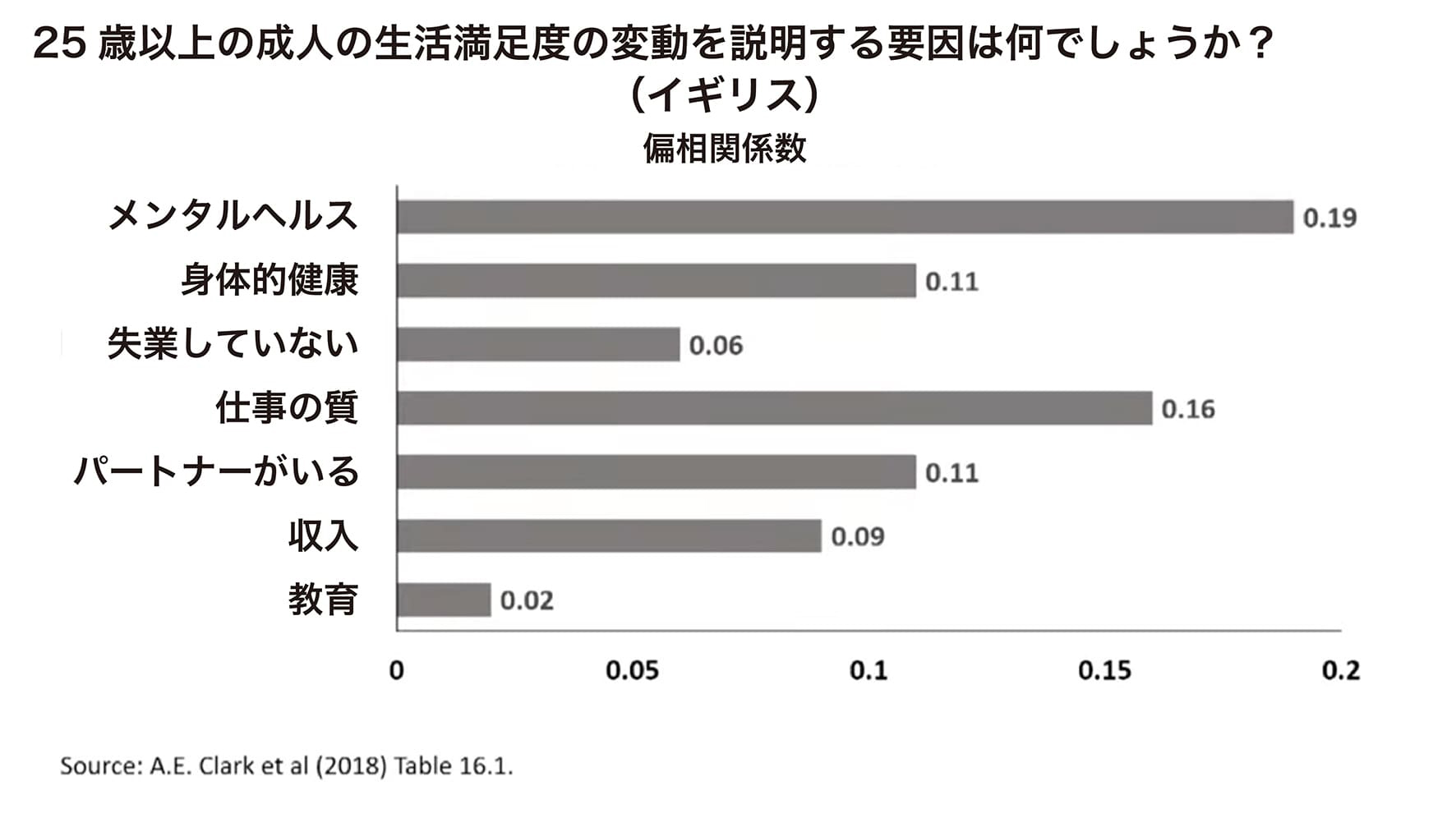

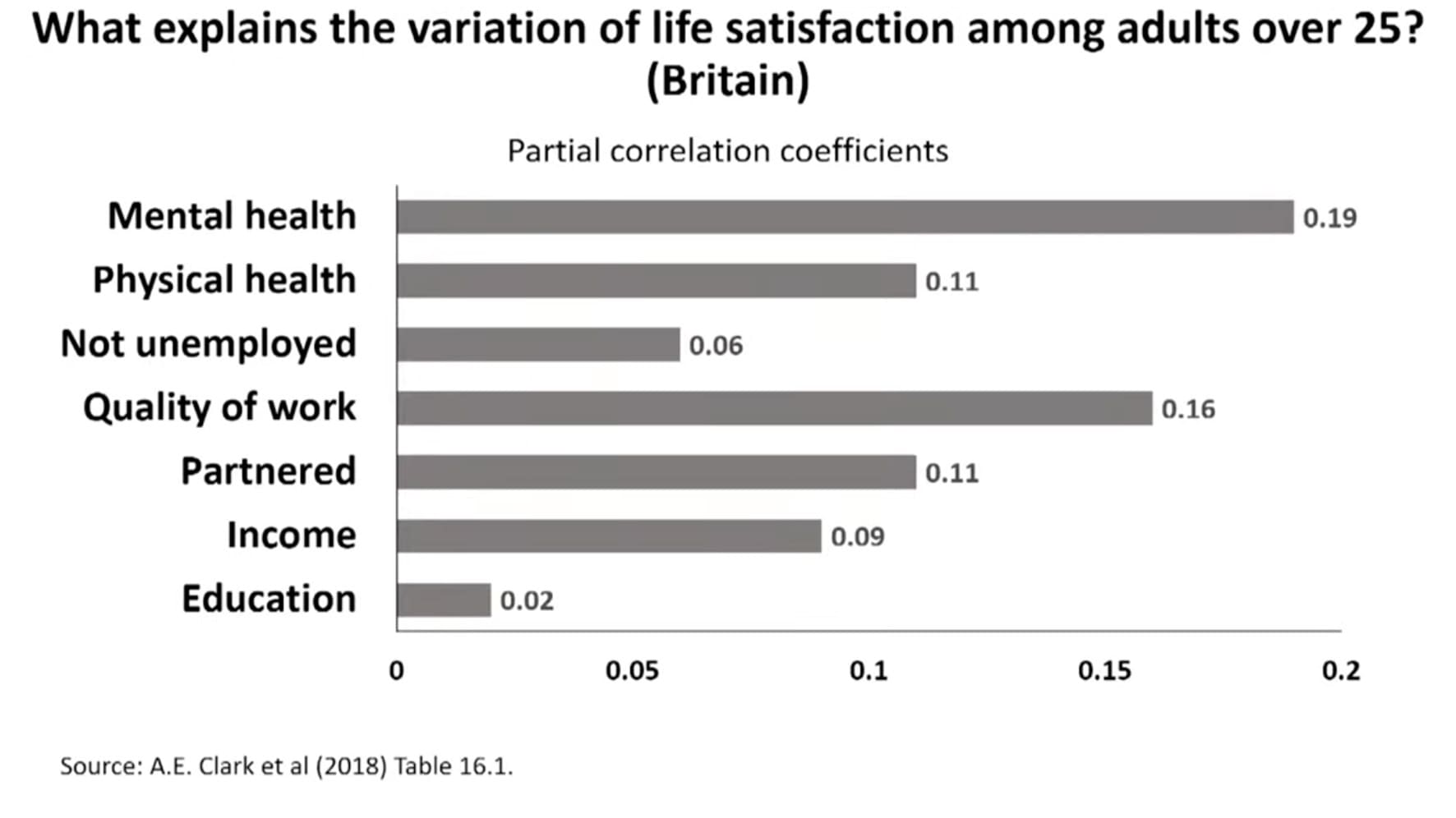

実際に国と国の間には、これらの大きな違いがありますが、実際には世界の幸福の変動の80%が国内─私たち自身を含む国内にあります。では、国内でのばらつきの原因を説明するのは何か、それを知りたい場合は、ばらつきを引き起こしている要因を知る必要があります。なぜなら、それは極端に低い数値を引き起こしている要因と同じだからです。それについての答えは、非常に多くの原因がある、ということです。そして、もちろん次のスライドで見るように、所得はとても貧弱な代理値です。

私が提示しているこのスライドは、各個人の生活満足度を説明するために見つけることができる、できるだけ多くの要因による調査を横断して方程式を推定した結果です。このグラフでは、各変数の影響を示します。それが、どれだけの説明力を持っているか。また、他のすべての要因を一定に保ちながら、それによる変動を説明します。

最大の要因は精神的健康であることがわかります。

それは次の質問への回答となります。

「過去に不安障害またはうつ病と診断されたことがありますか?」

身体的健康は、おそらくあまりうまく測定されていないかもしれませんが、重要です。家庭生活は非常に重要であり、雇用ももちろん重要であり、仕事の質、人間関係、そして所得を含みます。

しかし、これはこれらの変数を基に生活満足度の回帰を実行することから得られるものです。しかし、これらの変数の重要性を知る別の方法は、もちろん、人々に

日常生活で何を心配しているか?

を尋ねることです。驚くべきことに回答は、ほとんど同じランキングです。これは、ほとんどの政治家やジャーナリストが人々の生活に関する重要な要因と考えているものとは、まったく異なるものです。このパラダイムに基づいた新しい視点を得ることが、とても重要です。

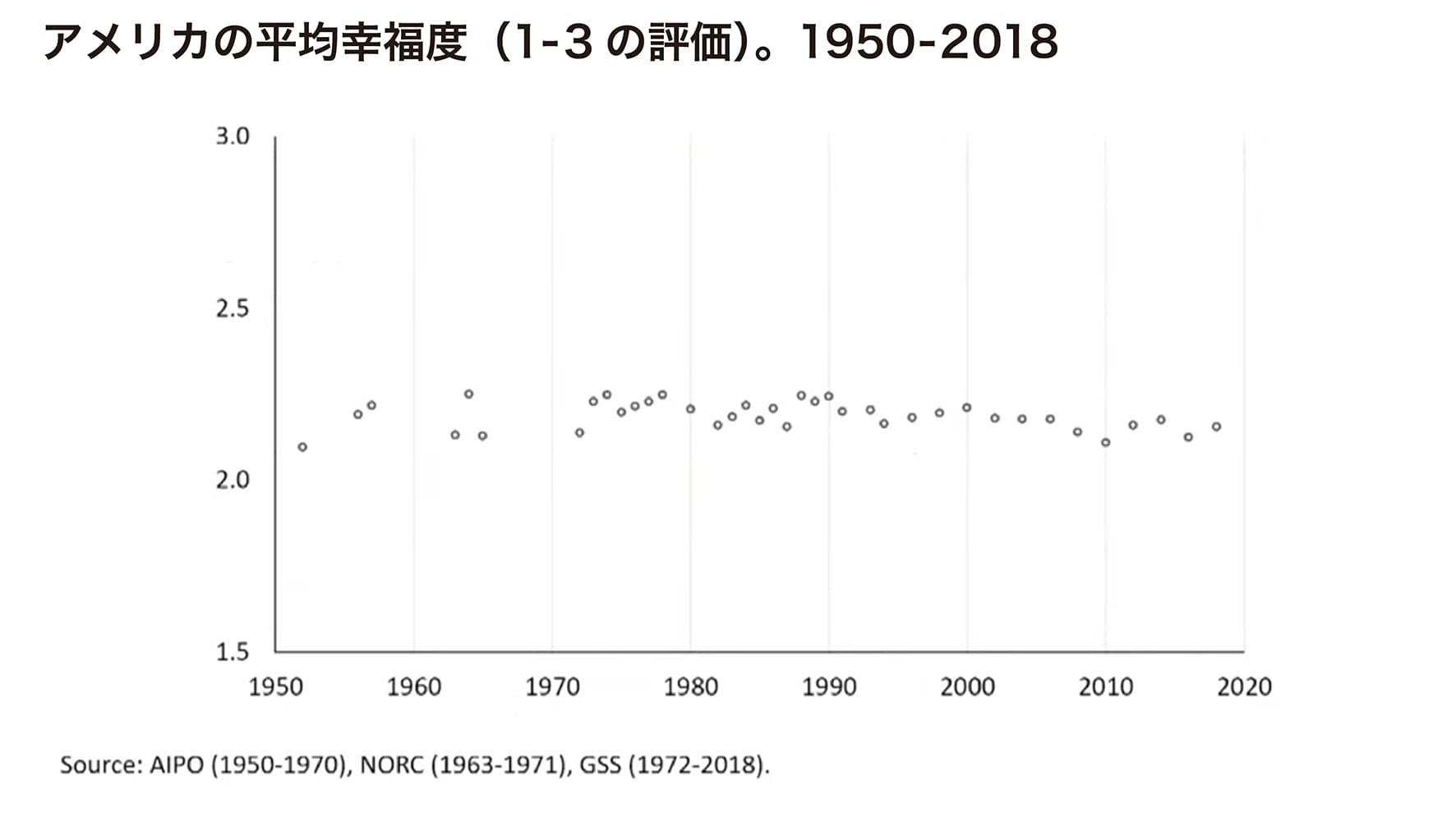

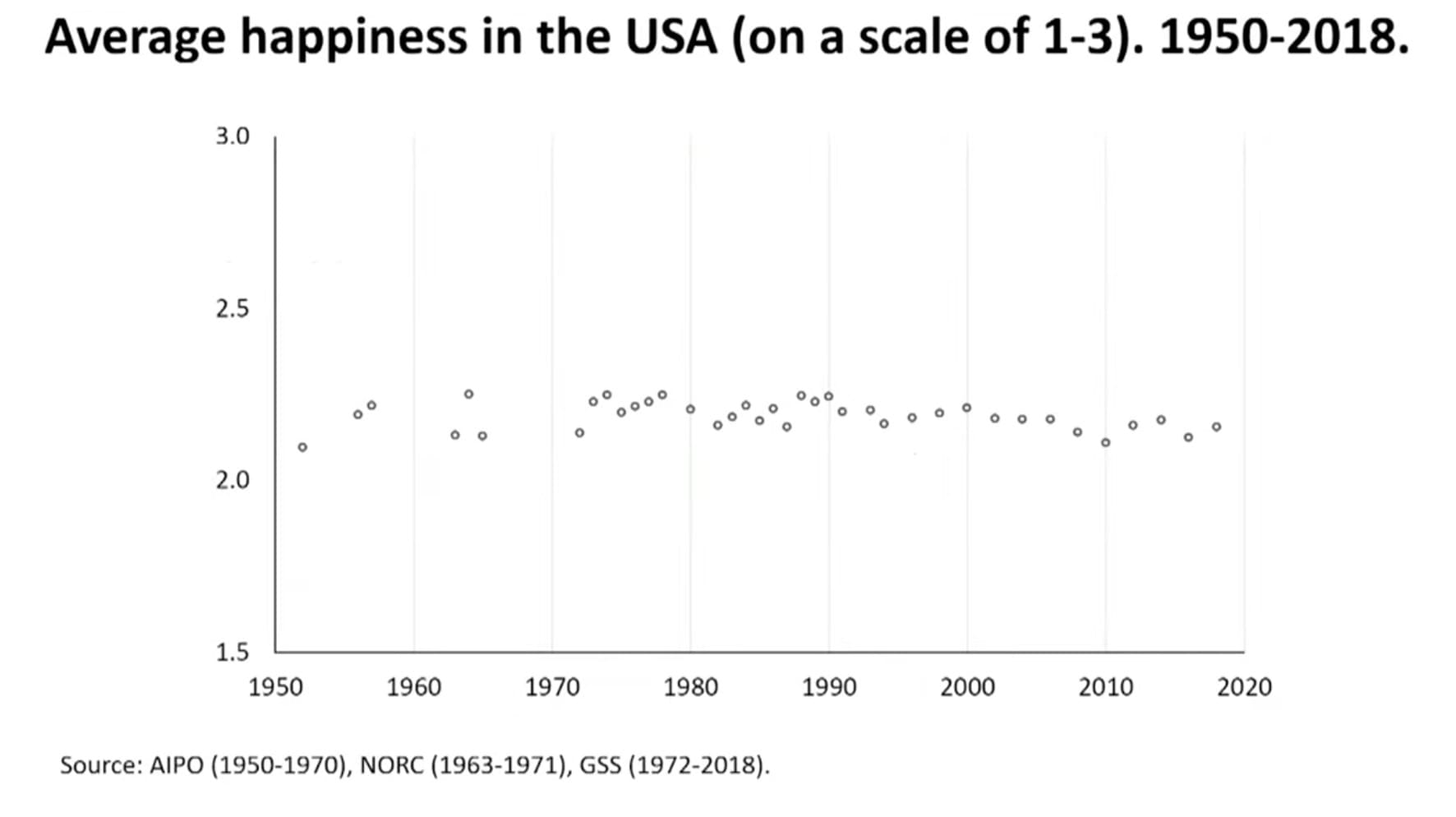

所得の位置づけは、多くの国で成長が幸福度の上昇が伴っていない、という事実を説明するのに役立ちます。

アメリカは最も顕著な例で、最も長い時間軸を持っていますが、ほぼ横ばいで、実際には終盤に向けてやや減少しています。ここでは、異なる要因が幸福に与える影響についての膨大な研究を議論する時間は、ありません。私たちの本に詳細に記載されているもので、この一連の知識は4つ目で、十分に強固であると私たちは考えています。ああ、すみません、飛ばしてしまいました。

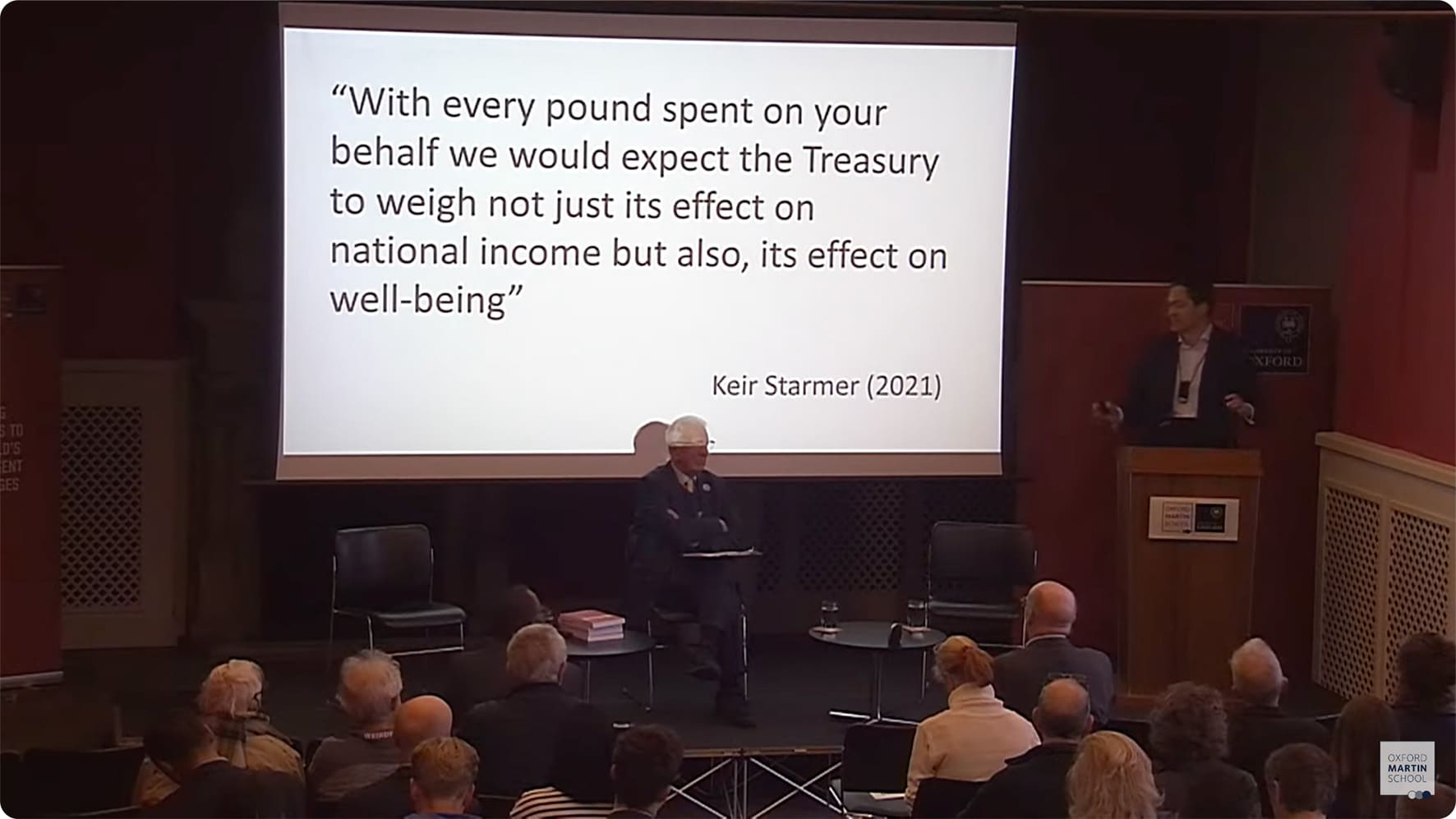

提案は、政策立案者がどれだけ予算をかけて幸福を増やすかに基づいて政策を判断すべきだ、というものです。これはOECDとEUが加盟国に求めていることであり、もちろん、キア・スターマーがこの発言をしたのは素晴らしいことです。

あなた方のために使われる1ポンドごとに、財務省には国民所得への影響だけでなく、ウェルビーイングへの影響も考慮されるべきです。それに刺激され、LLCの約6人は、それがどのように行われるかを示すのに忙しいです。そして、経済学者の皆さんに強調しておきますが、私たちは伝統的なコスト・ベネフィット分析を捨てているわけではありません。支払い意思・意向が明らかな証拠がある場合は、まだ使用できます。

しかし、意思決定から明らかにされることのない多くの他の政策の影響があり、これらは自己申告の幸福感を用いて評価する必要があります。そして、両方を組み合わせることができます。なぜなら、所得の限界効用がわかっているからです。

したがって、この方法を使用すると、従来のコスト・ベネフィット分析が不可能であった生活の広範な領域をカバーできます。そして、これらの分析は、もちろん主要な新しい優先事項を示唆するでしょう。私は精神的健康、子どもの幸福、若者の見習い制度に言及しました。

私は家族間の紛争や高齢者のケアにも、とても興味関心があります。これらのことは所得を増やすための、より明白なことと同じくらい重要です。だからこそ、公共支出全体を評価するために広範な幸福基準が必要です。マーティン・スクールが、これを実現するために主導的な役割を果たすために取り組んでくれたら素晴らしいですね。公共政策を分析するこの方法でリーダーにリードを提供するのは、ある意味完璧な立場にあると思うからです。

ジャンが、なぜ政治家にとってもそれが利益になるかを説明します。これから数年で幸福が政府の目標になることは疑いありません。そして、トーマス・ジェファーソンとジャン・ロックがこれを提唱してから200年以上が経過しているので、確かに時期が来ています。ありがとうございます。(👏)

チャード・レイヤード卿教授のお話の要点:

・デイビット・シュリグリーによる挿絵は、深いウェルビーイングを経験する新世界の必要性を指摘している。

・初めに述べたいことは、我々はウェルビーイングを目指す目的を受け入れなければならない。そのためには目的に合意する必要があり、政府は人々のウェルビーイングを向上させるために存在しているべきだとの立場を強調。

・幸福を公正に分配し、特に苦しむ人々のために条件を整える必要がある。

・ウェルビーイングの計測が必要であり、そのために広く受け入れられている質問がある。これにより、人類の状態に関する基本的な事実が明らかになる。

・世界のウェルビーイングは不平等であり、国内のばらつきが重要。政府の政策は人々が、どれだけ幸福になれるかに焦点を当てるべき。

・所得は幸福度上昇に伴って成長していない国があり、政策の評価にはウェルビーイングを基準に含めるべき。

・ウェルビーイングの調査は生活満足度を説明する要因を理解し、それに基づいて政策を検討する新しい視点を提供する。

3. ジャン=エマニュエル・ド・ネーヴェ教授から

リチャード、チャールズ、そして皆さん、素晴らしい特権と機会を与えてくれて、ありがとうございます。私たちの仕事と本を皆さんに紹介する機会に感謝します。私はリチャードの言った重要なポイントに基づいて、私たちが本で展開している洞察のいくつかを強調します。

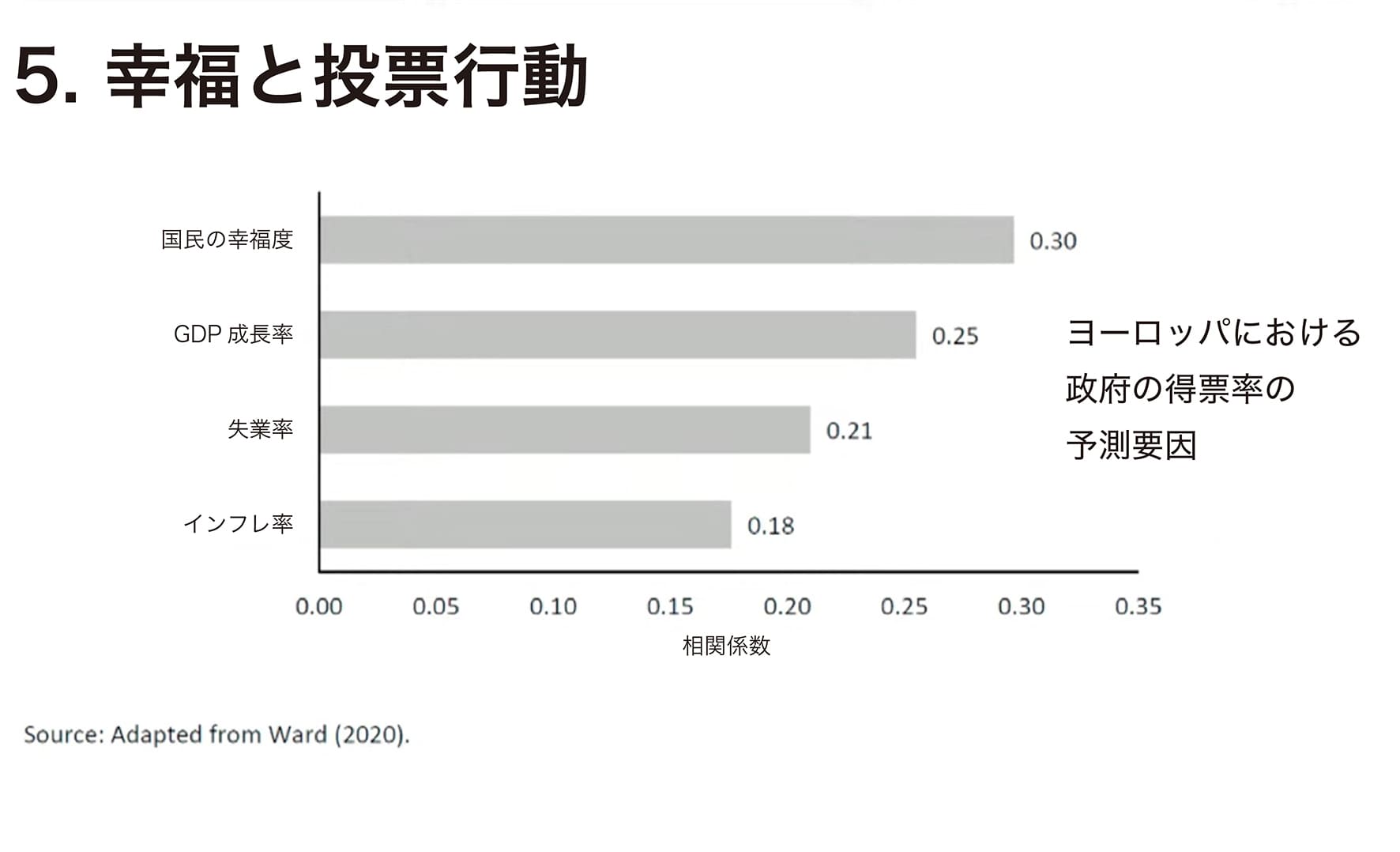

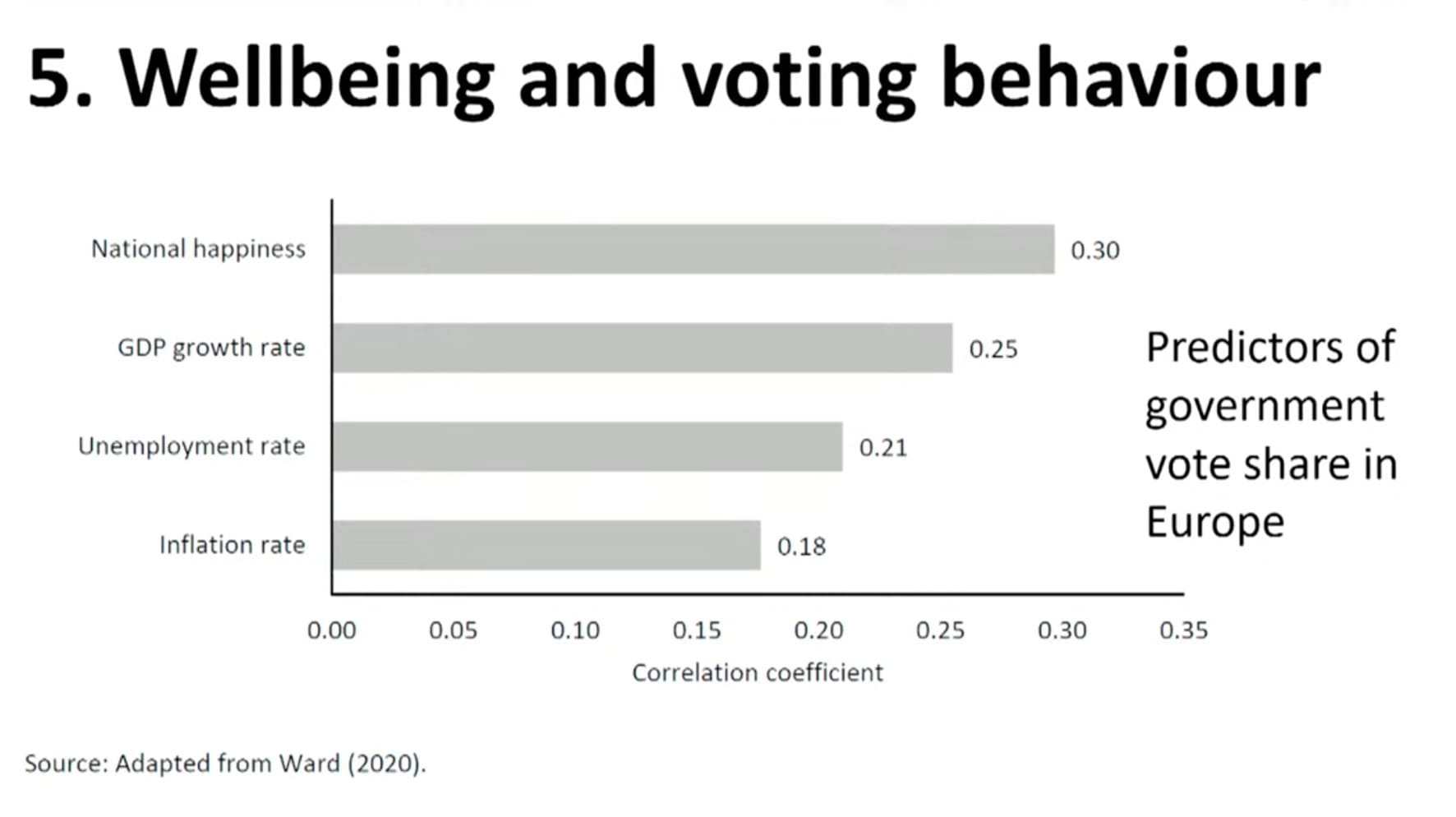

まず始めに、リチャードが重要な点を強調したことを踏まえます。政策決定の中心にウェルビーイングを据えるという道徳的な義務があるだけでなく、それが単に正しいことだけでなく、おそらく政治的に巧妙なことでもあるという証拠が今ではあります。

ここで進展したのは、私たちの元学生であり、今では親愛なる同僚であるジョージ・ウォードです。彼は4年前に、アメリカ政治科学ジャーナル(『American Journal of Political Science』)でとても重要な論文を発表しました。そこで彼は、すべてのヨーロッパの選挙を追跡し現職の得票率の変動と、それを幸福の変動と関連付けリチャードが紹介したその測定値と比較しました。

もちろん、GDP成長率、雇用または失業、インフレーションなどの従来の古典的な経済的投票時変数とです。ジョージが見つけた重要なポイント、なぜこれが重要なのか?は、ウェルビーイング、主観的ウェルビーイング、人々が自分の生活の質を評価する方法が、現職の得票率のより優れた予測因子であることです。

これを深く考えるほど、その論文を読んでみることをお勧めします。実際にはかなり直感的であることがわかります。選挙は客観的な周りの世界を取り入れる一方で、それを主観的なレンズを通して行います。そのため、私たちの主観的な幸福の尺度は実際に人々が経験する真実に、かなり近いものだと思います。

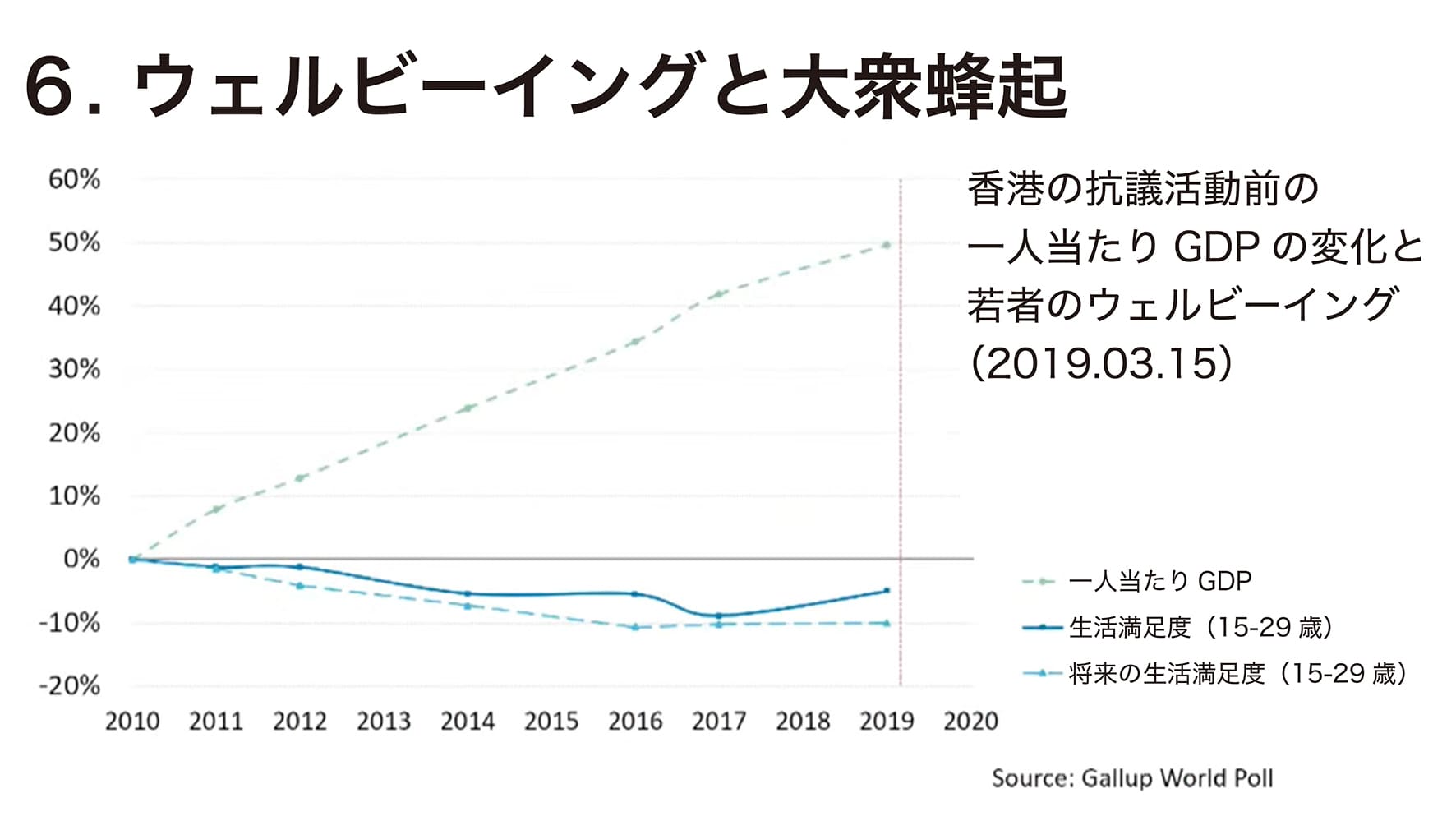

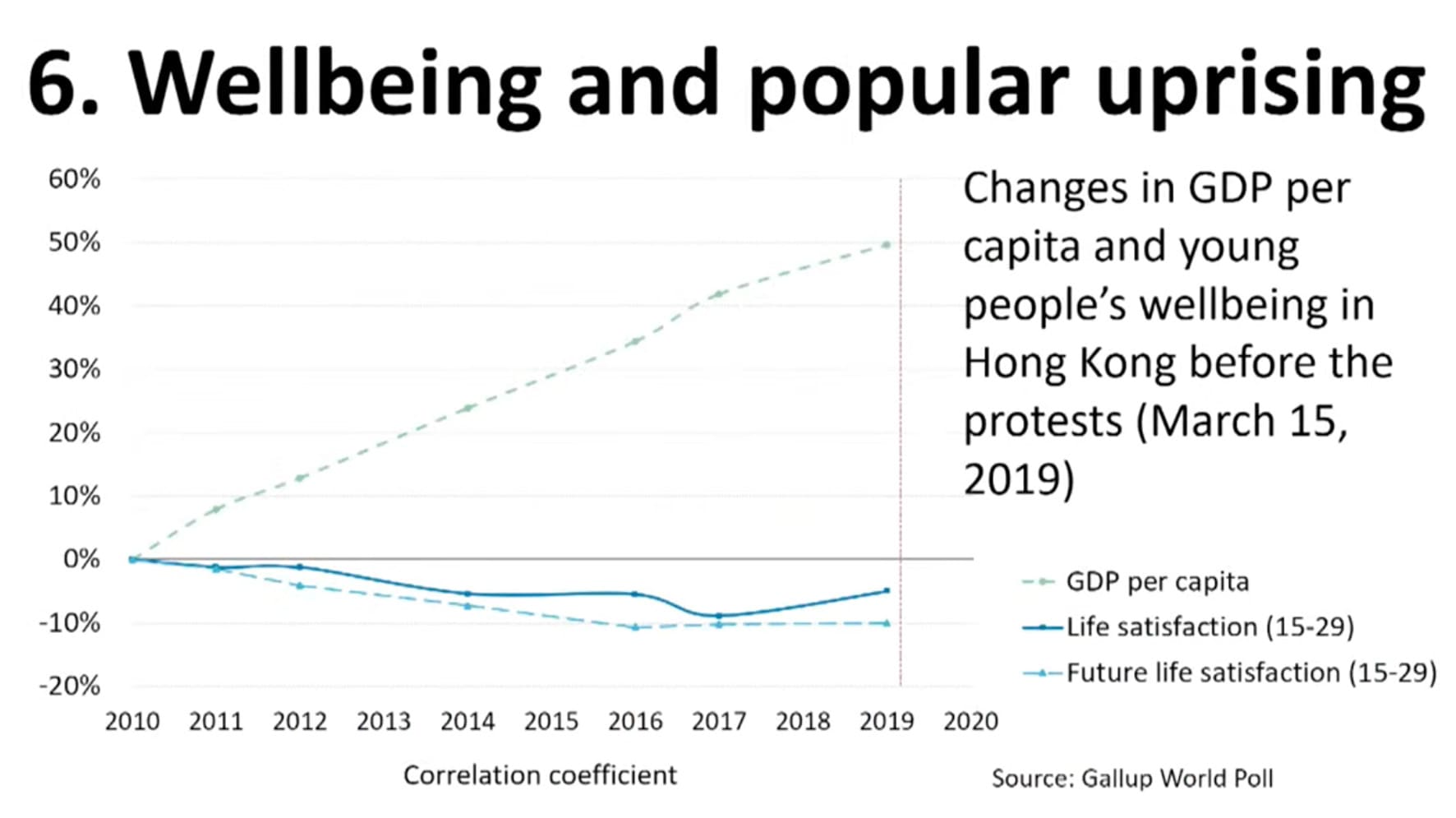

それは、政治的に巧妙なことであるだけでなく、特定の状況ではおそらく政治的に必要なことでもあります。ここで見ているのは、この本のために行った分析です。

2019年3月15日の香港の抗議活動が政治的議題、またはメディアの議題の焦点になった時点での分析です。したがって、潜在的な不安の予測因子としてのGDPを調査し、これがどのように社会的不安の予測因子と異なるかを調査しました。そして、香港はこの場合、単に経済データ、つまり一人当たりGDPを見ていたら、これが非常に素晴らしいニュースストーリーだと思っていたでしょう。わずか10年弱で、一人当たりGDPが約50%増加しました。

けれども、実際に香港の人々、特にこの場合は若者や若い世代がどのように感じているかを見ていたところ、人々が生活の質をどのように評価しているかは、かなりの低下が見られました。これは、アラブの春への導入で行った、この分析のインスピレーションを得ましたが、主観的ウェルビーイング、幸福の指標が伝統的なGDP指標が持っていない非常に強力な何かの要素があることを示しています。

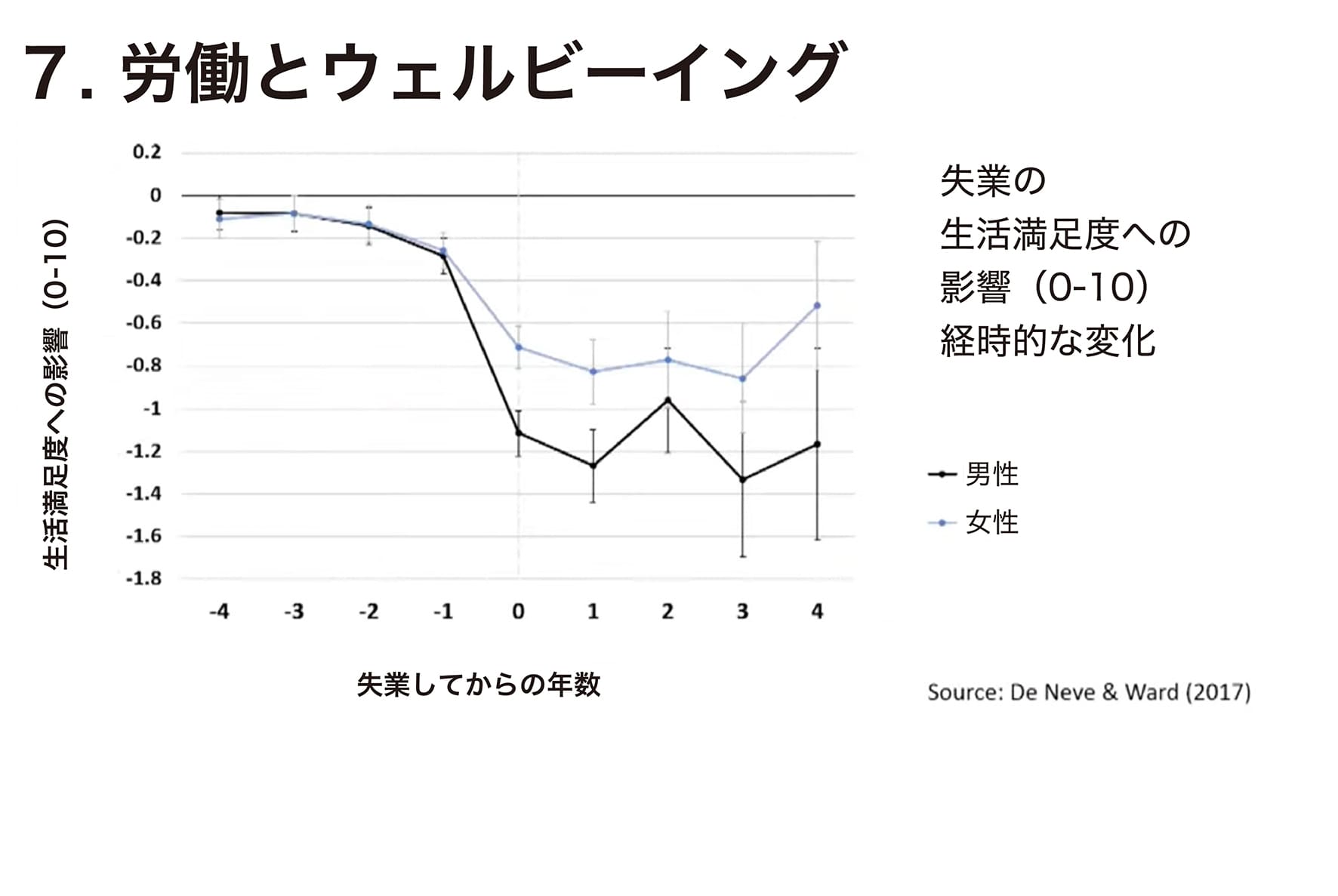

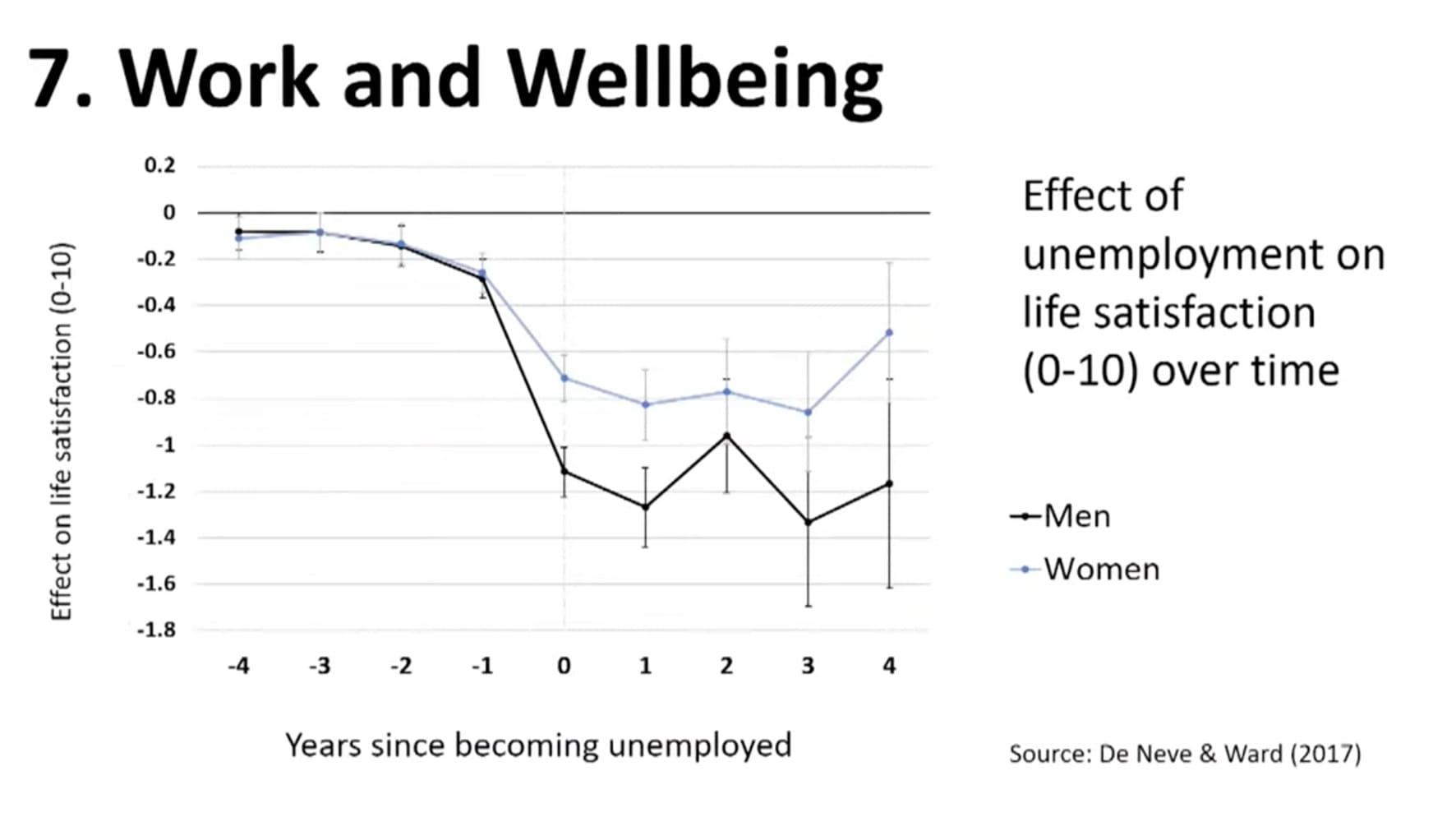

さて、私が主に研究の焦点としてきたのは、仕事の世界です。リチャードは、すでに職場が世界の総合的な幸福の重要な要因であると強調しました。しかし、それは本当にどれほど重要なのでしょうか? ここでもウェルビーイングの科学では多くの進歩があり、労働経済学や仕事の重要性についてもっと広く考えるのに本当に役立つと思います。

皆さんは仕事が重要だと知っています。これは給与──支払われる収入だけでなく、社会的地位、アイデンティティ、ソーシャルネットワーク、一日のルーティンなど、金銭的でない要素に関連しています。

これらがすべてが奪われた場合に、それが人の幸福にどのように幸福に影響を与えるかを示しています。ここで示しているのは、人々がリストラされる前とリストラされた後を見る時点のコホート研究です。明らかに「リストラ」という言葉は控えるべきであり、このような場合に使用すべきでない言葉です。

けれども、これは明らかに何が起こっているかを説明しています。ここで見ているのは、0から10までのスケールで

人々がリストラされると一点程度(男性の場合はさらに多く)幸福感と経験する生活の質が低下する様子です。

これは多いです、特に通常、平均の人々は英国の場合、6、6.5、7です。1点を失うことは大きなことであり、男性の場合はさらに、幸福感と経験する生活の質が約20%低下していることがわかります。これは巨大であり、おそらくこれはウェルビーイングの科学から出てきたキーの洞察であり、労働経済学に本当に追加された最も堅牢な洞察の一つでしょう。

男性と女性の間にはわずかな違いがありますが、「労働の重要性に従う主な本能は、失業に適応しない」という事実でもあります。ウェルビーイングの科学では、典型的には生活に対するショックが発生すると、それに比較的迅速に適応する傾向があります。ポジティブな人でも、ネガティブな人でも。人々がそれに適応することを予想しないであろうことでさえ、です。

しかし、仕事を失うことに関しては適応しないことが一般的です。繰り返しになりますが、これは主に労働経済学で強調された非金銭的な理由(例:地位やアイデンティティ、社会的ネットワーク、自尊心、職場での関係)のためだと考えます。これには現在、「失業の傷跡」と呼ばれる言葉があります。この種の科学、この種の結果は、特に経済の分野で政策立案者にさらなるプレッシャーをかけ、人々を働かせ、仕事の数量と質の両方で良い仕事をするようにできるだけ努める必要があります。

さて、これは幸福感と仕事の重要性についてですが、これを逆にできるでしょうか?

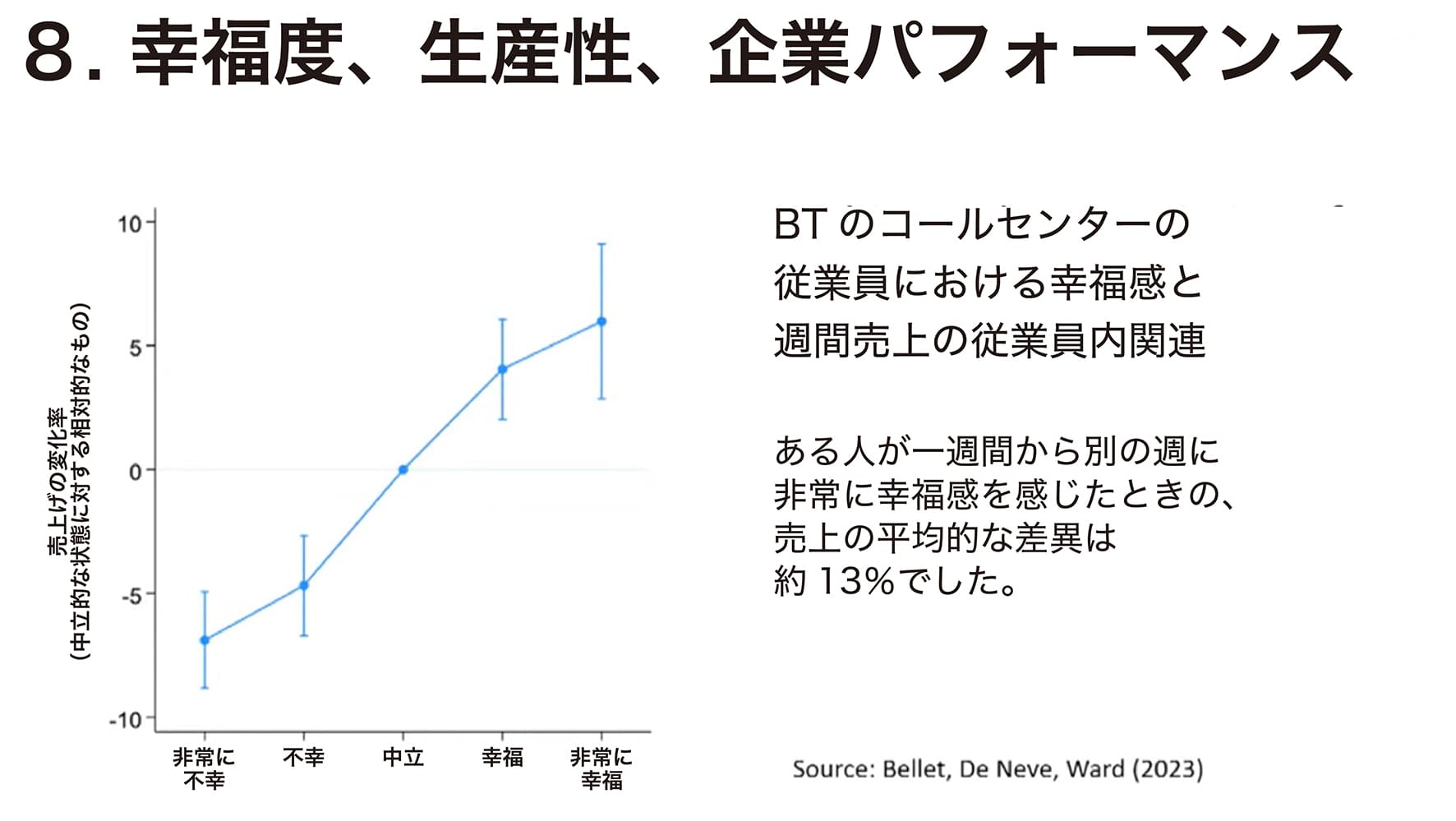

仕事での気分が私たちの仕事の質、個人のパフォーマンス、そしておそらく組織のパフォーマンスにどれほど重要かです。これについて私たちは過去数年間で、かなりの時間を費やして取り組んできました。

昨年、経営科学誌に掲載された論文を共有できて非常に嬉しいです。この論文には約7、8年かかりました。これは私たちが個人としてどのように感じるかと、それが私たちのパフォーマンスにどのように変換されるか、という関連についての初めての因果関係のある証拠を生み出すものだ考えています。この場合、具体的にはBT(British Telecommunications)のコールセンターの従業員を1週間ごとに調査しました。

彼らが一週間ごとに木曜日の午後4時にどのように感じているかを調査し、それを週ごとのセールス、顧客満足度、通話時間、通話回数などの非常に細かいパフォーマンスデータと関連付けました。ここで見ているのはメインの結果であり、これについては1時間話すことができますが、基本的に前週よりもずっと良い気分になると週間セールスが最大で12〜13%増加することがわかります。非常に具体的です。

これはちょっとした余談ですが、興味深いことに、あなたが行っているタスクの種類にも依存しています。感じ方の重要性が関わってくるのです。だから、これは平均的な効果です。

例えば、不満を抱いた顧客と取引し、そのビジネスを維持するよう求められた場合、一週間からもう一週間への感じ方の重要性は、これよりもはるかに重要でした。一方で、認めるべきことは、「注文を取るだけで社交性や感情の知性が必要ない場合、感じ方の影響はほとんどなかった」ということです。

ですので、職場のウェルビーイングに関与している方、また一般的に職場に関わっている方々にとって、

社会的および感情的な知性をどれだけ活用しているかは非常に重要です。

その成功は自分自身がどのように感じているか、に大きく左右されていることを示しています。そして、これは今までに示されたことのない方法で私たちが掴み取ったものです。

これは個人レベルでの話であり、個人の感じ方と仕事の質との間に非常に強力なリンクがあり、これは大きな組織にも影響を与える可能性がある1つのチャンネルであることをほのめかしています。これはこのような進行方法の一つです。他にも様々な方法があります。

従業員が気持ちよく感じる良い職場は、多くの人材を引き寄せる可能性があります。人々は口コミや他の場所から、それが良い職場であるかどうかを知る手段があるからです。従業員が気持ちよく感じる良い職場は、おそらく彼らの才能は長く保持されるでしょう。より多くの人材を引き寄せるでしょう。なぜなら人々には、その職場が良い場所かどうかを知るためのクチコミや場所があるからです。

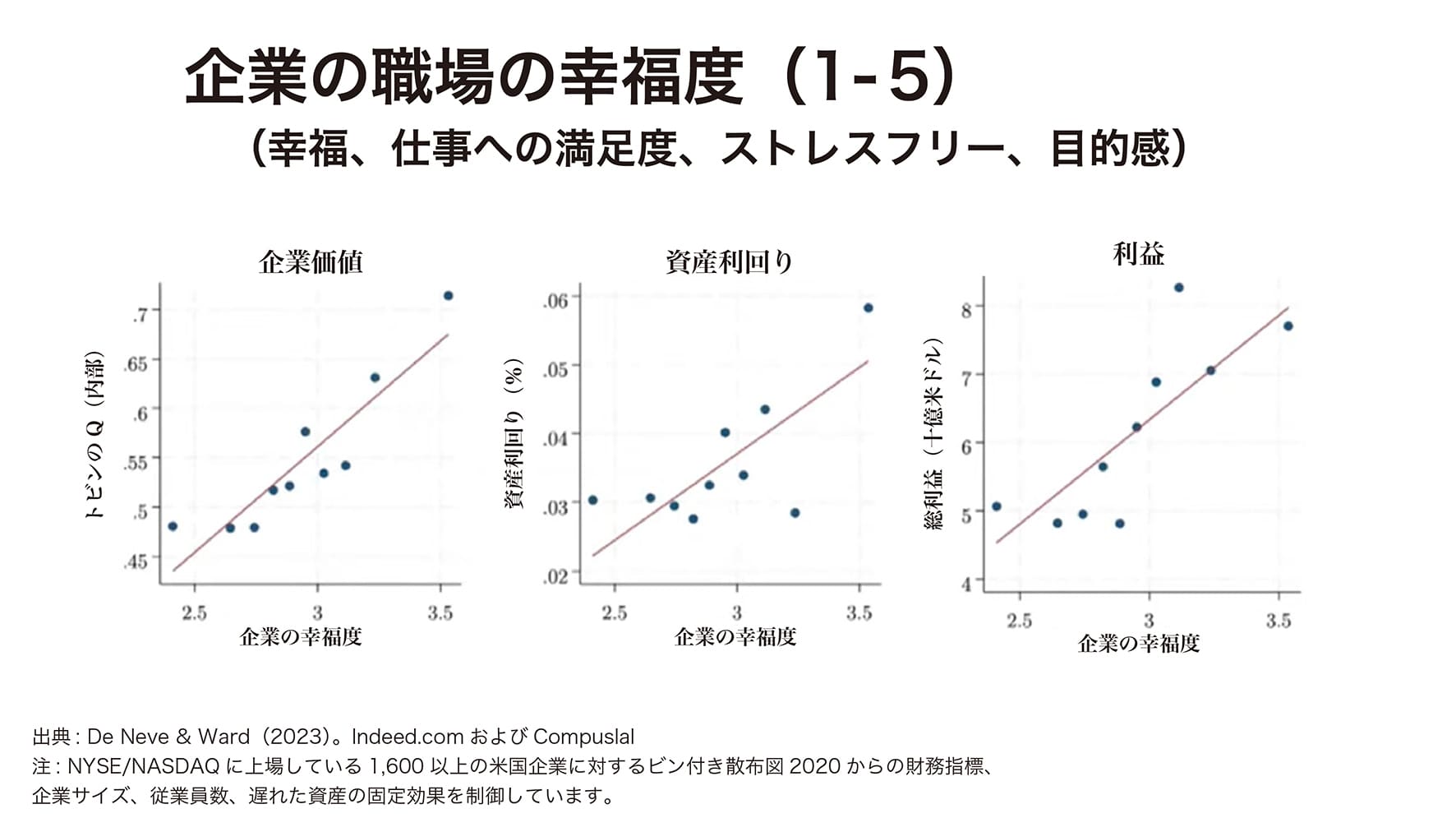

そして、これらのすべてのチャネルや経路が組織レベルでも関連しているのか、を示すことができるでしょうか?過去2年間、私たちは多くの研究を行ってきた結果を示しています。

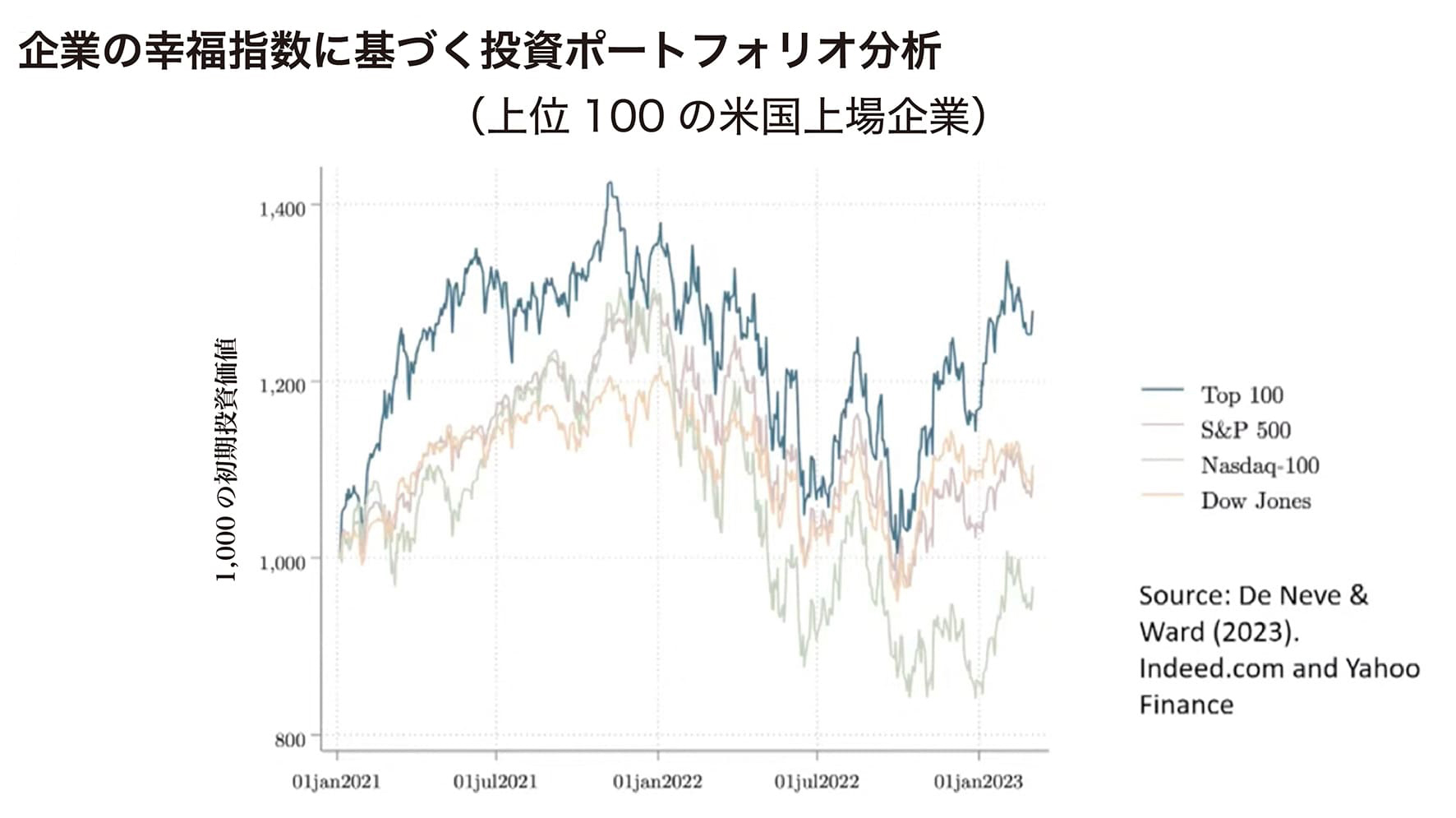

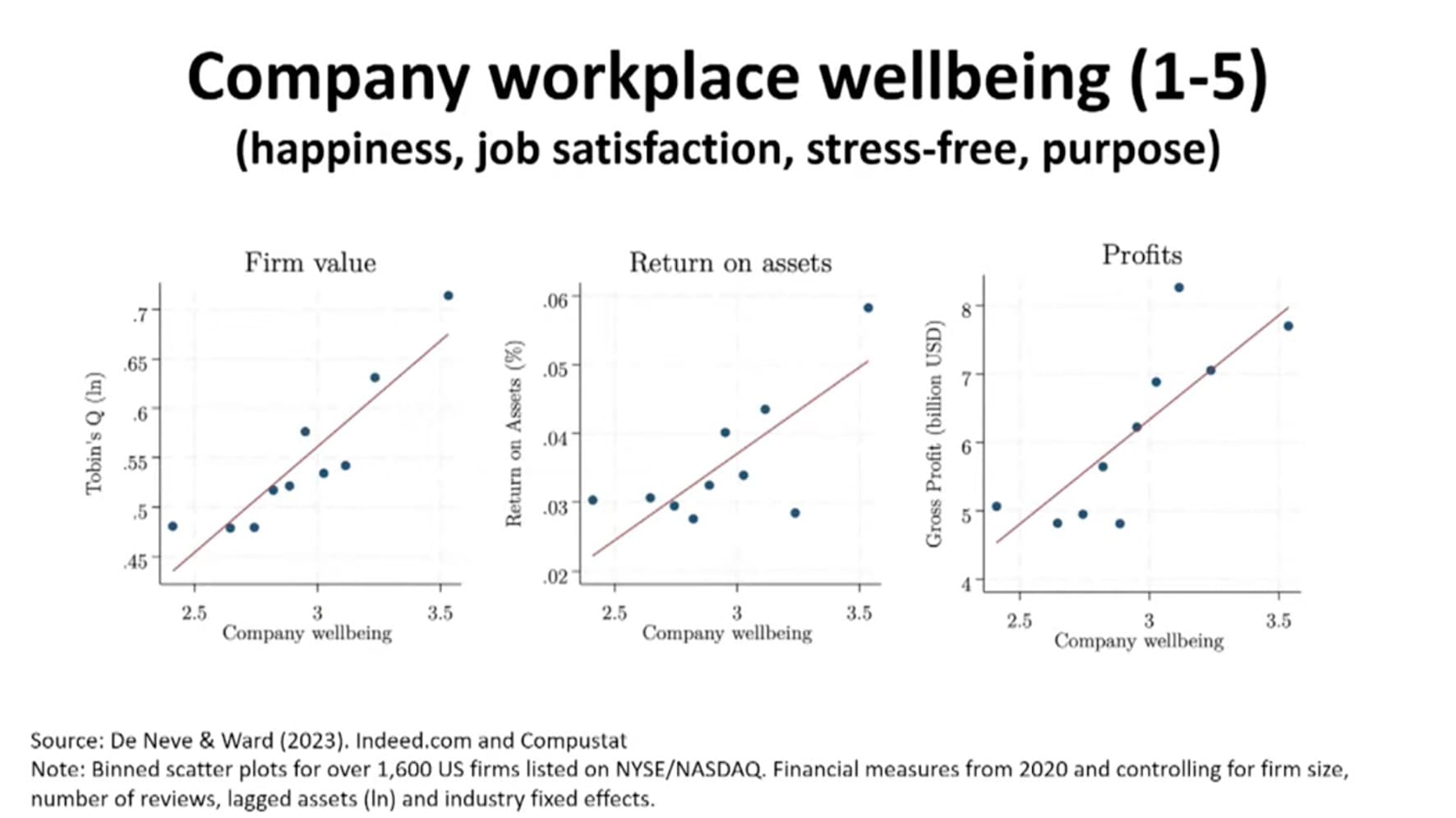

あなたがここで見ているのは、職場の幸福に関する世界最大の研究結果です。この場合、1,600以上の米国上場企業が含まれており、堅実なウェルビーイングのデータがクラウドソーシングされています。

Indeedなどのガラス張りのプラットフォームのおかげで、これらの企業が定期的かつ比較可能な方法で提供する必要がある四半期データに実際にリンクしています。ここで見ているのは、上位10%、下位10%、およびその間のピンです。従業員自身から戻ってくる平均的な企業の幸福度は、粗利益性、 総資産利益率、または企業価値のいずれであっても、主要な財務パフォーマンス指標と非常に強く関連していることがわかります。

これは明らかに同時的なものであり、これらは「組織としての仕事の感じ方」と、「それが組織のパフォーマンスにどのように影響するか」には確かに非常に強力な関連または相関があります。一歩進んで予測能力があるかどうか、を確認できるでしょうか?その一つの方法は、株式市場を見ることです。

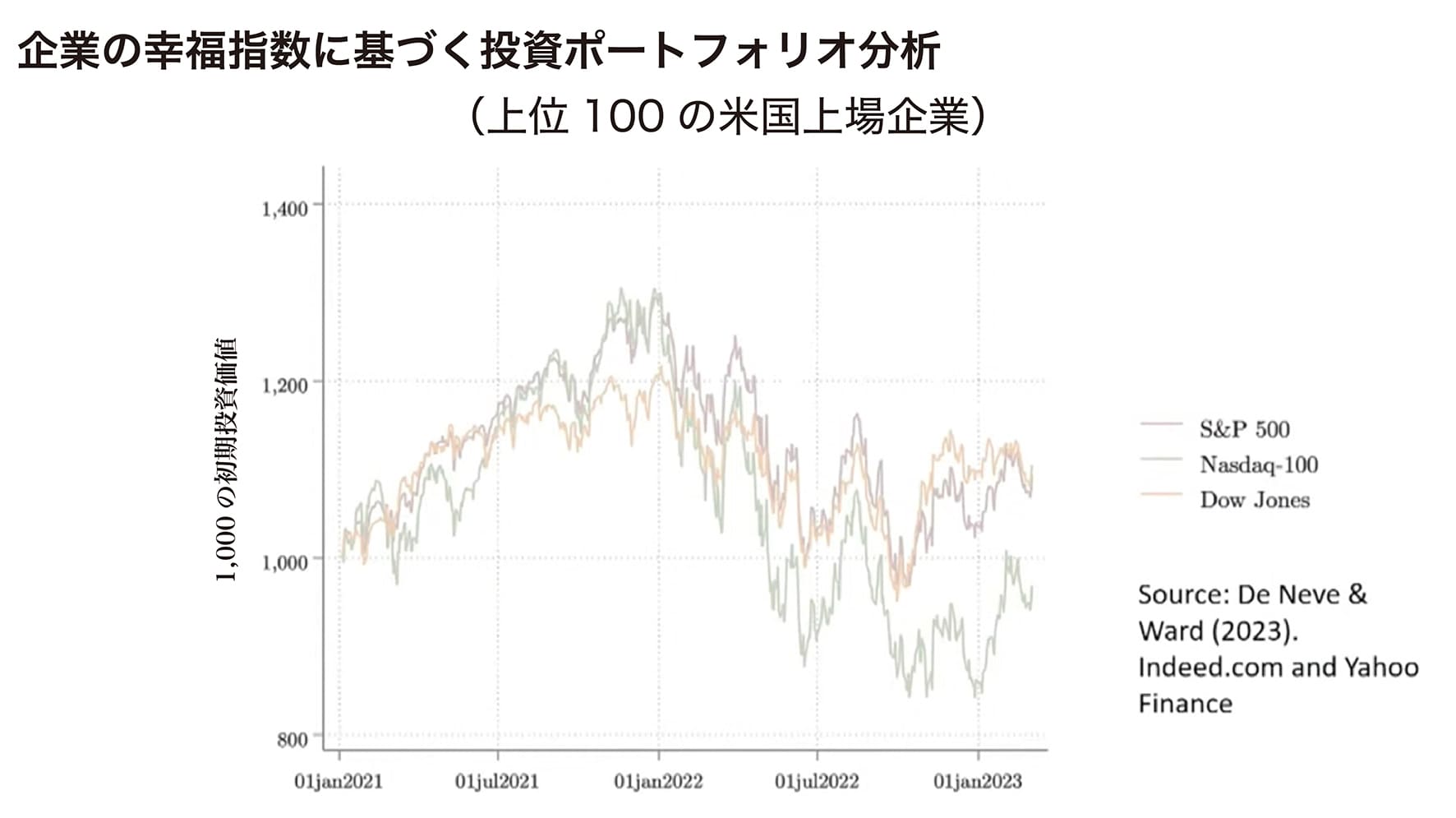

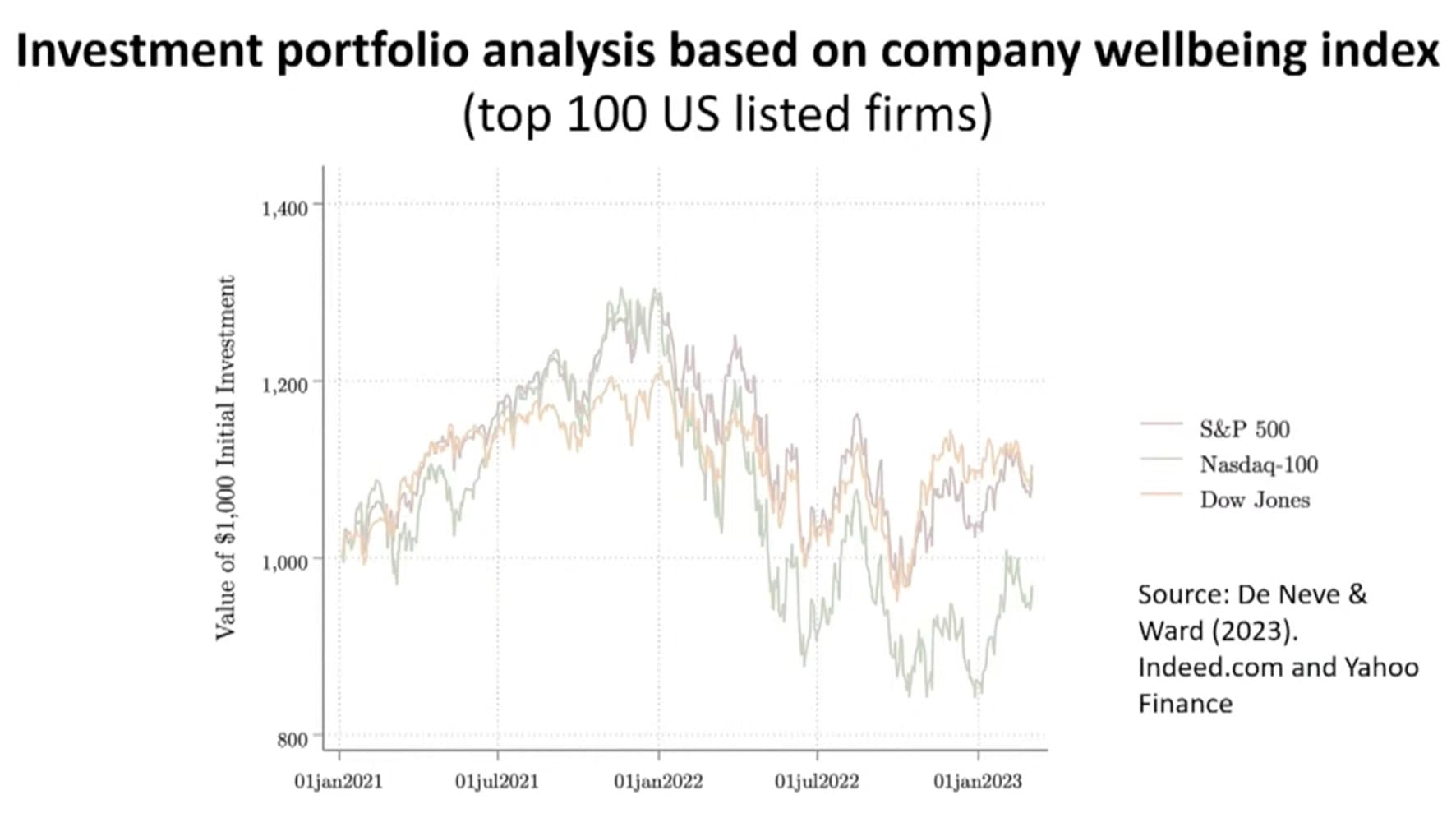

ここで見ているのは、メディアで注目されている分析です。非常に基本的なもので、ポートフォリオ分析と呼ばれています。株式に投資している方は、これに見慣れているかもしれません。次のように考えてみてください。たとえば、あなたが1,000ドルを投資するとしましょう。ほとんどの方はS&P 500などのインデックスファンドに投資するかもしれません。データがある数年間で、あなたの1,000ドルがどれくらいのリターンをもたらしたか、を見ると相当にプラスのものだったでしょう。これは多くの波乱があったにもかかわらず、です。

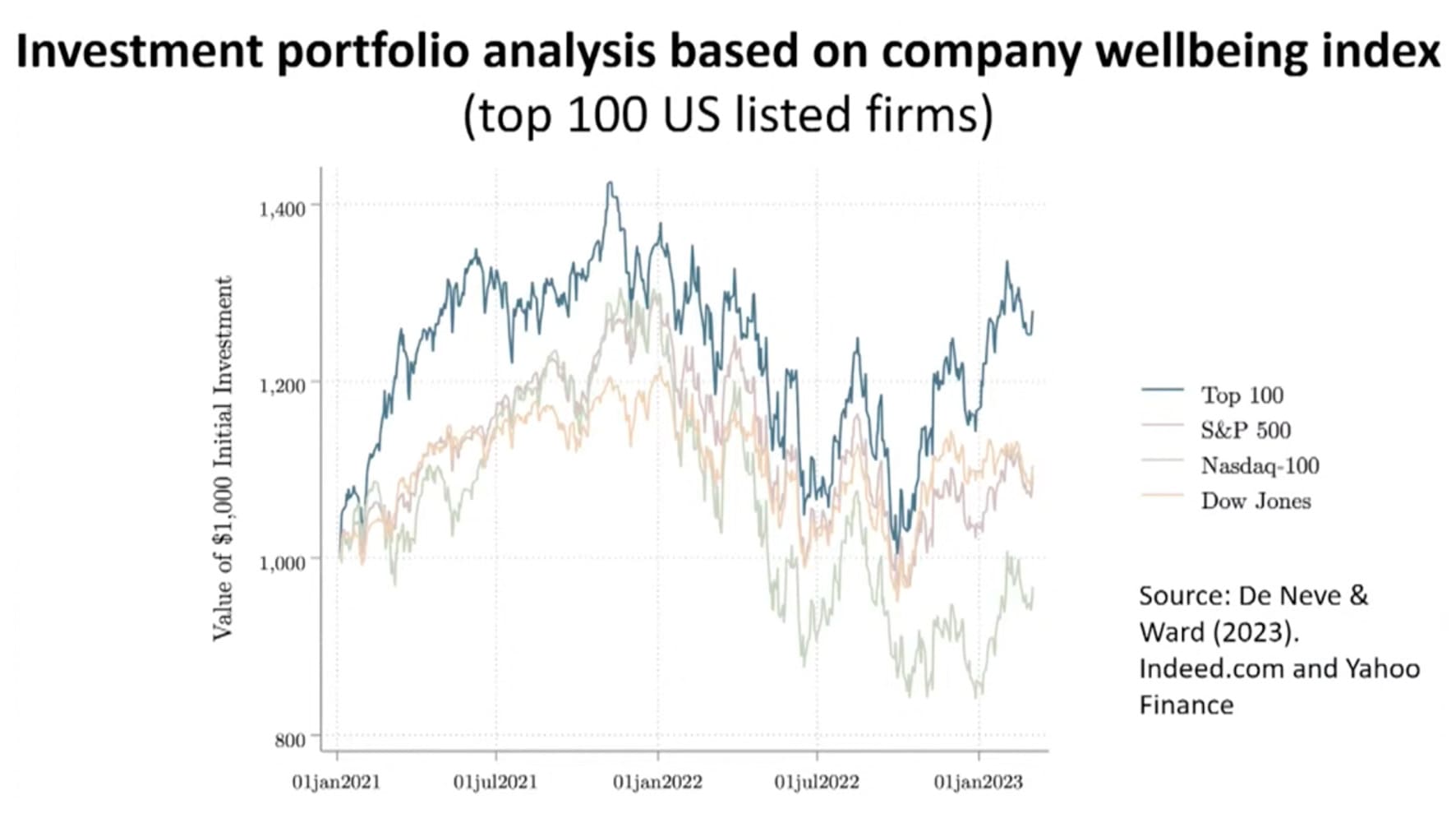

ここで見ているのは、2021年、2022年、2023年初頭で、伝統的なベンチマーク指数は上下し、2023年には価格や利益などの変動性や不安定性が発生しています。私たちが上場企業での人々の感じ方について持っている非常に優れたデータを使用し、これらをインデックスにまとめました。トップ100、トップ200、またはトップ50を取り上げ、それが株式市場で指標に対して良い成績を収めるするかどうか、を見てみましょう。

あなたが今ここで見ているのは、実に驚くべきもので、株式市場が従業員の感じ方の無形の要素の価値を完全には評価していないことを示しています。これは部分的には、これに関するデータへのアクセスがないことが原因かもしれませんが、それでも労働者の感じ方と、それが時間をかけてどのように収益に影響を与えるかの重要性を過小評価しているようです。

思い出してください。ここで行ったのは、2020年の職場の幸福度データをインデックスにまとめ、それを2021年1月1日から稼働させ、同様のことを2022年初頭と2023年初頭にも行ったものです。品質の高い職場に基づくポートフォリオは、すべての主要な指数を上回るパフォーマンスを発揮しました。リチャードが共有した内容が、あなたに興味を持ってもらえることを願っています。

それでも駄目な場合は、本を見てみることをお勧めします。なぜなら、そこにはデヴィット・シュリグリー氏による非常に素晴らしい挿絵があり、思考を刺激するものが本当にあります。それでは、これで終了しメインの画面に戻します。皆さん、お時間をありがとうございました。(👏)

ジャン=エマニュエル・ド・ネーヴェ教授のお話の要点:

1. ウェルビーイングの政治的な重要性

・ウェルビーイングを政策決定の中心に据えることは、道徳的な義務だけでなく、政治的にも巧妙な選択である。

・ジョージ・ウォードの研究により、現職の得票率と主観的ウェルビーイングの関連が明らかになった。

2. 香港の事例とGDPの限界

・香港の抗議活動において、GDPの経済的指標だけではなく、主観的なウェルビーイングの視点が不足していた。

・一人当たりGDPが増加しても、若者や若い世代の生活の質は低下していた。

3. 仕事と幸福の関連性

・仕事は給与だけでなく、社会的地位、アイデンティティ、ソーシャルネットワークなど非金銭的な側面も含む。

・リストラの影響を調査し、仕事の喪失が幸福感や生活の質に大きな影響を与えることを示した。

4. 仕事の感情とパフォーマンスの関連性

・仕事での感情が個人のパフォーマンスに影響を与えることを示す研究を紹介。

・職場の幸福が週間セールスに影響し、気分が良いと週間セールスが増加することを示した。

5. 組織のパフォーマンスと幸福の関連性

・米国上場企業に関する大規模な研究により、組織のウェルビーイングと財務パフォーマンスの強い関連性が示された。

・幸福な職場は組織の成功に寄与し、組織パフォーマンスと相関している。

6. 株式市場と幸福の関連性

・従業員の感じ方が株式市場での企業評価に、どれほど影響を与えるかの分析。

・幸福な職場は株式市場での企業のパフォーマンスにプラスの影響を与えていることを示唆。

7. 本の推薦

・本には非常に素晴らしい挿絵があり、デヴィット・シュリグリー氏による刺激的な内容が含まれている。

ジャン=エマニュエル・ド・ネーヴェ教授はウェルビーイングの重要性を政治的、経済的、組織的な側面から論じ、具体的なデータや研究結果を交えて説明しています。

4. Q & A

チャールズ:さて、質問から始めます。

Q. 今年は選挙があります。オックスフォード大学のマーティン・スクールは無党派であり、スターマーかスナクかファラージかは、わかりません。しかし、選挙の数日後に電話がかかってきて、「お金がありません。比較的迅速に、人々の生活に影響を与えるために何ができるか?」と尋ねられた場合、それに対してどうすればいいかを教えてください。

リチャード: 実は最初に三つのことがあるのですが、まず第一にこの政策は、ウェルビーイングを志向したものであり、ホワイトホール全体で、何が政府の政策の優先順位として考えられるかを変えたいと思っています。

次に、お金がないと言っていますが、実際にはお金を節約するのではなく、むしろ費用以上に多くのお金を節約するいくつかの政策があります。私は、今ではNHSと呼ばれる会話療法を開発し、それが不安障害とうつ病の治療に使われています。私たちは、障害者給付金から開放して人々を仕事に就かせることで、税金を支払い、また、NHSにおいても物理的な国民健康保険の身体的健康管理のコストを削減することから、それが元のコストをはるかに上回る節約になることを示すことができました。

私たちの社会と家族に大きな混乱をもたらしている依存症と人格障害のためのサービスを求めています。これらの治療は困難ですが、その代わりになる節約はさらに大きくなります。それが私の第二の提案です。

第三に、この国が学校を卒業した後の人々にどのように対応しているかが、本当に恥ずべきことだと思います。私たちには、大学に行かない場合でもアクセスしやすい、適切な職業訓練や見習いのシステムがありません。これは恥ずべきことです。私は見習いへの確実なアクセスを求めています。

ジャン: 素晴らしい。科学がメンタルヘルス、職場や、リチャードが強調したすべての政策が非常に重要であることを示しています。私はリチャードに加えて、社会インフラで知られていることを言い換えます。実際にインフラを手に入れましょう。政治家は常に道路、HS2(高速鉄道計画)、電車などに投資したがりますが、それはもちろん必要なことですが、社会インフラを無視するか、あるいはその犠牲にするべきではありません。

社会資本、社会の信頼、多くの場合、私たちが失ったものが、人々が思っている以上に重要であることがわかります。たとえば、私たちの世界幸福度報告書では、国と国の間の変動を説明する要因を見ると、収入などが多くの役割を果たしています。ですが、最も強力なのは社会的なサポートである傾向があります。社会資本、ボランティアの機会、お互いへの信頼、機関への信頼などです。だからこそ、これにはまだ多くの仕事が残っており、それはGDPに直接的には影響を与えないため見過ごされがちです。

Q. 選挙後、予算不足で電話がかかってきた場合、何ができるか?

リチャード卿の提案:

1. ウェルビーイング志向の政策を優先し、政府の政策の優先順位を変える。

2. お金を節約する代わりに、費用以上に多くのお金を節約する政策を導入(例: NHSの会話療法)。

3. 依存症と人格障害の治療サービスを拡充し、その代わりになる節約を実現。学校卒業後の適切な職業訓練や見習いのシステムを確立。

ジャンの補足:

・社会インフラを強調し、社会の信頼やサポートが重要。社会資本の向上、ボランティア機会、お互いへの信頼の構築が必要。

・社会資本はGDPに直接影響しないが、重要であることに留意が必要。

チャールズ:では、ウェルビーイングのアプローチに挑戦する人々について質問させてください。

Q2. あなたは自分を新しい功利主義者と表現しましたが、功利主義は過去の100年でさまざまな意見がありました。権利、能力などに関連する多くの学派があり、あなたの細かい分析の多くには賛成できるでしょうが、包括的な功利主義の枠組みが不利な立場の人々の権利に影響を与えることを心配している人たちもいます。あなたは本でこれについていくつか触れているのは知っていますが、新しい、現代の功利主義者とは何かについてもう少し詳しく説明していただけますか。

リチャード:ジェレミ・ベンサム(イギリスの哲学者・経済学者・法学者。功利主義の創始者)は、「目標は単に人口全体の幸福度の合計または平均であるべきだ」と提案しました。私は、この種のアプローチを取る現代のほとんどの人が、プリンストン大学の著名な功利主義者であるピーター・シンガーを除いてですが、同じことをするためには「出発点が低い人を1単位だけ上に動かすことが、出発点が高い人を同じことをするよりも重要であるはずだ」と感じています。だから、これは、この枠組み内で社会正義のアイディアを表現する方法に導くものだと思います。

社会正義のアイディアは、低い立場から始める人々に優先権を与えるべきだとされています。ただし、これはもちろん、単に所得だけでなく、はるかに広い概念の「低い出発点」が必要です。後でそれについて触れても良いかもしれませんが、これが私の功利主義の概念であり、ウェルビーイングの分布に敏感な方法で適用されているという考え方です。

チャールズ:ただし、経済的功利主義の利点は、議論の余地がないところにあるお金に関する指標があるところです。

Q. けれども、より洗練されたアプローチを取る場合、異なるバックグラウンドやステータスを持つ人々の利益をどのように評価する関数を実際にどのように定義するのでしょうか?

リチャード:もちろん、これは問題です。人々がこれに対する見解は異なり、これは規範的で倫理的な問題です。私たちは、学者が政策立案者が価値をどのように実現できるかについて話しています。もちろん、政策立案者が平等主義者であるかどうかを評価するパラメータを使用して数学的な価値を書き留めることができます。しかし、もちろん数学に疎い政策立案者にとっては、別の方法として異なるウェルビーイングの出発点を持つ人々に対する政策の影響を反映し、異なる政策を検討して政策立案者が自分の判断を使用して選択できるようにするのがより直截的です。

Q1: 選挙後に生活に迅速な影響を与えるための提案

・リチャードの回答:

・ウェルビーイング志向の政策

・費用以上に多くのお金を節約する政策

・依存症と人格障害の治療へのサービス強化

・学校卒業後の職業訓練や見習いへのアクセス向上

Q2: ウェルビーイングのアプローチに挑戦する功利主義者について

・リチャードの回答:

・現代の功利主義者は低い出発点から始める人々に優先権を与えるべき

・社会正義のアイディアを低い立場から始める人々に適用

・ウェルビーイングの分布に敏感な功利主義の概念

・経済的功利主義の利点はお金に関する指標があること

Q3: 異なるバックグラウンドやステータスの人々の利益を評価する関数の定義

・リチャードの回答:

・規範的で倫理的な問題

・数学的な価値を使用して政策の影響を評価する方法

・政策の影響を反映し、政策立案者が選択できるようにする直截的な方法

・異なるウェルビーイングの出発点を持つ人々に対する政策の影響を比較

チャールズ:ありがとうございます、ジャン。質問してもいいでしょうか?

Q. このアプローチには左派からの批判もありました。左派の人々はしばしば金融からウェルビーイングへの転換に喜んでいますが、一部の分析は所得分配の役割を過小評価している可能性を心配しています。あなたが提示したいくつかの要因が幸福と相関しているかもしれませんが、実際には所得と分配の基本的な影響を隠しているかもしれません。そして、私は、人々が言っているのを聞いたことがあります。ウェルビーイングの問題は、経済の中で根強い権力関係の一部を隠してしまう可能性がある、と。

ジャン:これは難しい問題ですね。 まず第一に、左派からの批判として出てくることに驚くでしょう。なぜなら、ウェルビーイングと主要な結果は実際にの限界効用が減少させることだからです。経済学の観点から見ると、進歩的な課税と再分配に関する中道左派の議題に非常に適しています。なぜなら、私たちが非常に明確に発見したのは、主観的な幸福に対しては、100万ドルを稼ぐ人が1万ドルを得るよりも、1万ドルを稼ぐ人が追加の1万ドルを得るよりも少ないということです。これはかなり確立されており、通常は使用されない累進課税の新しい視点や観点、正当化を提供してくれます。それで、それが議題の一部を助けると思います。

また、ウェルビーイングの議題は保守派の側面にも役立つ可能性があり、それが非常に興奮する理由です。これは左右、中道の人々が共感できる議題です。もちろん、GDPや所得は一部の要素の背後にあるかもしれません。例えば、教育がウェルビーイングに肯定的な影響を与える場合、それは社会経済的地位やその背後にある権力と富の影響かもしれません。けれども、本の中で科学を掘り下げ、私たちはこれらの欠落した変数を取り除く因果推論を試みて探しています。

Q1: ウェルビーイングアプローチの左派からの批判

・ジャンの回答:ウェルビーイングは進歩的な課税と再分配に適している

・限界効用が減少している観点から議論

・累進課税の新しい視点を提供

Q2: 所得とウェルビーイングの関係

・ジャンの回答:所得は重要だが、限界効用の観点から複雑

・限界効用の減少は明確で、左派にとって大きな洞察

・科学的な取り組みで欠落した変数を取り除く因果推論

Q3: アリストテレスの「徳のある生活」について

・リチャードの回答:アリストテレスの幸福の理念に一部否定的な見解

・徳のある生活が個々と社会の幸福を増やす重要性に言及

チャールズ:ありがとう。リチャード、私は生物学者なので、明らかにアリストテレスは英雄の一人です。本の冒頭では、アリストテレスと彼の幸福の理念や「徳のある生活」について少し否定的であったように感じました。しかし、本の後半で、あなたが個々の幸福だけでなく、社会全体の幸福も増やすための「徳のある生活」の重要性について話したときに新たな理解が生まれました。

Q. 徳のある生活は、個人の幸福を増すだけでなく、より広範な社会の幸福に寄与する要素として考える余地があるのでしょうか?

リチャード:もちろん、あなたが最後に言ったことは正しいですが、問題は目標が何かということです。アリストテレスの素晴らしいところは、もちろん、「異なる行動の価値を比較するために使用する唯一の目的が必要であるというアイデアを持っていたこと」です。それは素晴らしいアリストテレスのアイディアです。

アリストテレスの問題は、その後、目的を「善い経験」を徳の一種の混合物と定義したことです。しかし、これは問題を完全に解決していません。私たちは徳を、人々が人生を楽しんでいる社会の手段と考えるでしょう。ただし、各人が自分自身の幸福を促進することにしか関心を持たない場合、人々が自分の人生を楽しんでいる社会は存在しません。

人々が他の人々の幸福を向上させるために多くのエネルギーを費やすことが、人々が自分の人生を楽しんでいる社会の手段です。徳は目的への手段です。もちろん、それはある程度、徳のある人にとって報われる影響があります。

ジャン:徳は主に、みんなに良い結果を生み出すために提唱されるべきです。そして、それについてコメントさせていただくと、私はここでリチャードが最後に言ったことが重要だと思います。徳はある程度、自己の報酬です。素晴らしい証拠があります。NHS 会話療法のボランティアと一緒に行われた研究では、もちろん彼らが助けている人々の助けになりますが、ある程度それは彼ら自身にも助けになります。

ですので、私たちが政策を導くための究極の基準として幸福を設定するなら、それは徳の行動も包括していると言えるでしょう。

私が今、自分自身のクローン(複製)を作るとしたら、一人の自分が他の人に親切なことをした場合、そしてもう一方の自分が別の個人に悪いことをした場合、善行を行った私のバージョンはより良く感じ、より高い人生の満足度を持つはずです。そのため、これは幸福度の測定を最上位に配置するための裏付けとなるでしょう。それは徳行動をある程度、完全ではないかもしれませんが、ある程度取り入れているからです。

Q: 徳のある生活は社会全体の幸福に寄与するか?

・リチャードの回答:

・アリストテレスのアイデアは目標の定義に問題がある

・徳は社会の手段としての価値がある

・徳のある人が他の人の幸福を向上させることで報われる

・ジャンのコメント:

・徳は自分自身の報酬であり、NHSのボランティアの研究で裏付けられている

・幸福の基準として幸福度を設定するなら、徳行動も包括すべき

チャールズ:時間経過に関するウェルビーイングについて質問してもよろしいでしょうか? あなたは今、ウェルビーイングが現在の投票の傾向にどのように影響するかについて驚くべき結果を示しました。そして、政治家は選挙の直前に予算を配る必要がさらに強まると考えられるでしょう。したがって、おそらく将来に対するそのような行動のトレードオフを考慮したウェルビーイングの尺度が必要です。

本であなたはまた気候変動についても話しており、これは将来のすべてのトレードオフの母であると指摘しています。あなたはウェルビーイングについて、経済学と同様に将来をより価値のあるものとするアプローチを取るが価値を割り引くと主張しています。

私は2つの質問を持っています。まず、経済学の文献を見ると、

割引率に関する仮定が政策の結論にかなり依存していることがやや心配です。例えば、ノードハウス対スターンのようなものです。問題は未来が非常に大きいため、割引率の基点の変更が巨大な影響を与えることです。これらの問題をどのように解決していますか?

リチャード:将来の評価に関連する問題は確かに重要です。割引率の違いが政策結論に与える影響は大きいため、その扱いは慎重である必要があります。従来の経済学では割引率は通常、将来の価値を現在の価値に変換する手段として用いられますが、将来への価値をより高く見積もる必要性があるという立場をとっています。

しかし、将来の大きな不確実性やリスクを考慮することが難しいことも確かです。未来がどれだけ価値があるかを定量的に測定することは難しく、割引率の正確な決定も難しい課題です。そのため、異なる割引率やアプローチを取る経済学者の意見が分かれています。

ノードハウスとスターンのようなアプローチの比較においては、将来のリスクや環境への影響をどれだけ重視するかがポイントとなります。これらの問題は複雑であり、異なる状況において適用されるべきであるという立場もあります。

総じて、将来の評価においては様々な要因を考慮する必要があり、単一の割引率やアプローチが全ての状況に適しているわけではないとされています。

割引率の基本的な概念は、経済学者や財務省などが使用するもので、純粋な時間的好意と不確実性との関連性があります。これにより1.5%が生じ、それに加えて、経済成長により人々が豊かになると所得の限界効用が低くなるとの仮定があり、それにより2%が加わります。このため、合計で3.5%となり、これは2100年の1ポンドが現在の私たちにとって6ペソの価値しかないことを意味します。つまり、世紀末は忘れてしまってもよいとされています。

気候変動の動きに反対したエコノミストがこれに依拠していたのです。その意味で無駄だったのは収入を基準として考えることで、収入は人々にとって重要なものではないからです。もし彼らの社会全体がひっくり返り、移動し、到着することによって他の多くの人々が混乱するなどがある場合、その他の多くの側面も考慮する必要があります。

ウェルビーイングの観点から考えれば、私たちは1.5%しか残りません。これにより、将来の世代に対するより真剣なアプローチが可能になります。つまり、私たちが「どの人々のウェルビーイングが重要か」と言及する際、将来の世代のウェルビーイングも私たち自身と同じくらい重要であると言いたいと考えるでしょう。けれども、すべてが無限に評価されてしまうため、論理的な問題に直面します。したがって、割引の要素が必要ですが、確かに高すぎてはなりません。

ジャン:しかし、それは確かに大きな違いを生む要素となります。リチャードが美しく表現したとおりです。もしもウェルビーイングを真剣に考慮し、それを政策決定の中心に据えるならば、それは気候変動や環境の課題にも対処するのに役立ちます。なぜなら、リチャードが述べたように、将来の世代のウェルビーイングを、従来の経済アプローチが行うよりも遥かに少ない割合で割り引くことは避けたいからです。リチャードは全く正しいです。従来の経済的アプローチでは現在、英国政府の費用対効果分析には3.5%から4%が組み込まれています。これはつまり、その場合、何年後か75年後では2100年をはるかに超えることはありません。けれども、もちろん、将来の世代とそのウェルビーイングを考える際には超えるべきです。

Q1: 将来の評価とディスカウント率に関する問題

・リチャードの回答:

・将来の評価に関する問題は重要

・割引率の扱いは慎重でなければならない

・異なるアプローチや割引率の意見があり、状況によって適用されるべき

・ジャンのコメント:

・割引率の違いが政策結論に大きな影響を与える

・現行の経済的アプローチでは割引率が高すぎる可能性

・ウェルビーイングを考慮すると、気候変動や環境の課題に対処しやすくなる

・将来の世代のウェルビーイングを少なく割り引く必要性

・具体的な割引率の例:

・経済学者や財務省は純粋な時間的好意と不確実性を考慮し、割引率を設定

・例: 3.5%の割引率では2100年の1ポンドは現在の6ペソの価値に相当

・従来のアプローチでは将来の世代のウェルビーイングを低く評価

・ウェルビーイングの重要性:

・ウェルビーイングを真剣に考慮することで、将来の世代のウェルビーイングへのアプローチが向上

・従来の経済アプローチでは適切な評価が難しいが、ウェルビーイングの導入で対処しやすくなる

チャールズ:聴衆へのQ&Aに移る前に、最後の質問があります。これは部分的には皮肉っぽいものですが、同時に真剣なものでもあります。

Q1. 今晩、美味しい赤ワインを開ける予定で、私のウェルビーイングが段階的に向上するでしょう。それは美徳的なことなのでしょうか?

Q2. そして真剣な質問は、本に取り上げられている批判であり、有名なオルダス・ハクスリーの「すばらしい新世界」の問題です。もし私たちが主観的なウェルビーイングを向上させる薬を作り出したとしたら、それはアリストテレスの徳のある人生に逆らうものであり、詐欺的な手段で達成されるものです。オルダス・ハクスリーの「ソーマ(すばらしい世界の中に出てくる錠剤)」の問題にどのように立ち向かいますか?

リチャード:まず最初に言いたいのは、もし誰かが何の副作用もなく、通常よりも良い気分になる薬を発明した場合、なぜ私たち全員がそれを摂取しないのでしょうか? 私たちは生活を楽しいものにするためにさまざまな方法で日常を工夫しています──異なる食べ物、薬を含めることに何が問題があるのでしょうか?私はそれに何の問題も見いだせません。彼は、そこで全く違う方向を見ていたと思います。

おそらく鍵は、何かが素晴らしいと感じるものでも、依然としてトレードオフが存在する可能性があるということです。素晴らしいと感じるものには引き続き、トレードオフがあるかもしれません。全く仕事に行かなかった場合でもトレードオフになる可能性があります。

ジャン:チャールズ、あなたのボトルの赤ワインが完璧な例です。適度であれば効果があるかもしれませんが、過度に摂取すると翌日に悪影響が出る可能性があります。

チャールズ:私には裏付けとなるいくつかの実験データがあります…(笑)。

Q1. ジョーク的な質問:

・赤ワインを開けてウェルビーイングが向上することは美徳的か?

・リチャードの回答: 生活を楽しむ方法は様々で、良い気分になる手段は問題ない。トレードオフがある可能性も。

Q2. 真剣な質問(オルダス・ハクスリーの問題):

・主観的なウェルビーイングを向上させる薬について

・リチャードの回答: 何かが素晴らしいと感じるものでも、トレードオフが存在する可能性。問題は適度な使用と過度な使用のバランス。

赤ワインに関するコメント:

・赤ワインが適度であれば効果があるかもしれず、過度な摂取は悪影響をもたらす可能性あり。

チャールズ:では、聴衆の方、質問がありますか? マイクが届くのをお待ちいただければと思います。録音されていることを念頭に置いておいてください。手を挙げてくださる方はいますか?クララ、正面にいらっしゃる方から始めていただければと思います。マイクが届くまでお待ちいただければと。

──ありがとうございます。私はあなたが行っているすべての大ファンです。私は感情の知性の分野で働いていますが、あなたのコメントを伺いたいと思います。

Q. 私たちは科学と政策について話しています。政策を作成するには、あなたが言及した究極の判断基準、そして私がすべてのグラフや物事に照らして判断するための基準が必要です。生活満足度とウェルビーイングが入れ替わっているように見えます。実際、ある人は人生の満足感が一番下にあり、ウェルビーイングは主観的ウェルビーイングでした。他の人はどこにいてもウェルビーイングでした。それらを定義しない限り、それはあまり役立たないように感じます。私は2007年の幸福カンファレンスに参加していました。今はもっと多くのデータがあります。これが私の最初のポイントです。明確である必要があると感じています。

リチャード:この本は主に生活満足度についてであり、それは世界幸福度報告書で使用されている概念であり、最も使われ、最も研究されている概念です。それは、人々が評価的なウェルビーイングと呼ぶもので、自分の人生に対する感じ方についての判断の要素が含まれています。ここでは難しいですが、自分の人生についてどう感じているかは、あなたがその瞬間に感じていることとと全く同じではありません。それはご存知のようにヘドニック、快楽的と呼ばれるものです。私は人々が時間の積分にわたってどのように感じているかを測定することは、明らかに大規模な研究課題です。

まず第一に、それをあなたの究極の基準として持つことには多くの問題があります。例えば、夢を含めるべきか?意識に関連するさまざまな問題があります。この科目はまだ初期段階にあると思います。これがこの形で行われているのはせいぜい40年で、現時点では特に政策の分野では、警察サービスや交通システムにどの程度満足していますか、と人々に尋ねることに非常に慣れています。あなたが自分の人生にどれだけ満足しているか、試してみてください。

1. 質問のポイント:

・科学と政策の議論において、明確で簡潔な判断基準が必要。

・主観的ウェルビーイングと生活満足度の関連性が議論され、それが不明瞭であれば有益ではないとの指摘。

2. リチャードの回答:

・本は主に生活満足度に焦点を当てており、それは世界幸福度報告書で使用されている概念。

・主観的ウェルビーイングは人々の評価的な感じ方に関連し、研究が進む中で概念の定義や測定が進行中。

3. 注意喚起:

・主観的なウェルビーイングや生活満足度を究極の基準にすることには問題があり、その測定には様々な課題がある。

・現在の研究では、感じ方を測定するための標準的な手段が確立されていない。

チャールズ:ありがとうございます。この部屋には多くの専門知識があることはわかっていますが、質問は短く、話者からの発言を聞けるようにしてください。それからオンラインからの質問に移ります。短く簡潔に話します。

──私は非軍人ですが、サイバーインテリジェンス(情報通信技術を利用したスパイ活動)のアドバイザーであり、軍の慈善団体の指導者でもあります。私のキャリアで恐ろしいことを見てきました。確かにサイバーセキュリティでは、かなりひどい出来事が人々に起こっています。これほど短期間で私に本当に考えさせられました。

Q. 治安は人々の生活にとって非常に重要で、私には治安の欠如はガザ、ウクライナに関して否定的であり、逆に積極的な治安は中立的であるように思えます。ただ単に安全な生活を送っている人々が幸福を経験できるという証拠があるのかどうか。

ジャン:それは難しい質問ですね。質問をいただきありがとうございます。あなたは全く正しいと思います。もちろん戦争が起こるまでは治安は幸福にとって基本的です。多くの研究が、安全な環境やコミュニティ、広い範囲の環境で安心感を感じることと生活満足度・幸福感との強い関連性を示しています。これは身体的な安全性だけでなく、経済的および社会的な安全性も含みます。個々の人が自分の生活のさまざまな側面で安心感を感じると、それは全体的な幸福にポジティブに影響を与えます。ただし、この関係は複雑であり、異なる個人は彼らの経験や視点に基づいてセキュリティの重要性を異なるように評価する可能性があります。

時々、私たちは「世界幸福度報告書」に対して、ある国は戦争がない限りあまり変化しないという批判を受けますが、もちろん戦争が勃発すると急激に低下します。したがって、私たちが現在準備中の「世界幸福度報告書」では、イスラエル・ガザ・ウクライナのデータに詳しく触れています。昨年もウクライナについて詳細に調査しました。不安定な状況では幸福感が大きく低下するのがよく見られます。

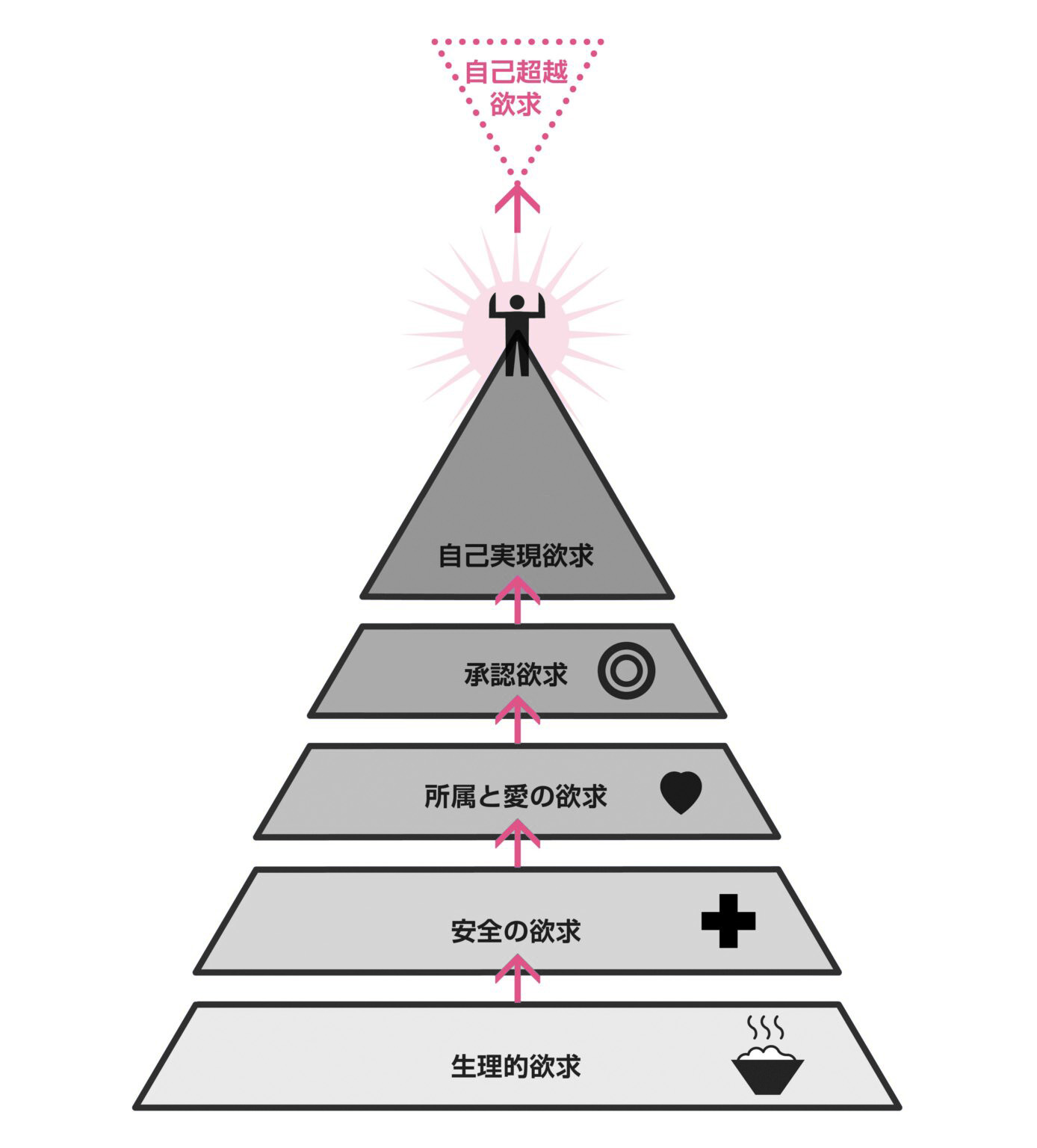

アフガニスタンもその例で、2年前の出来事はひどかったが、今は最下位になっています。アフガニスタンの平均報告された生活満足度は10点中2点にも満たない。これは平均であり、つまり、もし1人が5点と言った場合、それをゼロにするには別の10人が必要です。不安定な状況は非常に大きなダメージを与えますが、確かに安全な基盤があったら──金持ちの人たちは、私がこれを言ったことを嫌うでしょうが、おそらく他のことについて考え始めるかもしれません。ただし、マズローの欲求ピラミッドには疑問があります。

マズローの欲求5段階説

リチャード:質問を許可していただけますか?マズローについて触れましたが、安全のあらゆる側面を考えてみてください。つまり、食料の安全性があり、暴力からの安全性があり、拘束からの安全性があり、家族関係の安全性は妻が裏切らないか、子供たちが元気か、あなたは宇宙の中であなたの場所は大丈夫だと感じるか、などの次元があります。したがって、安全性のあらゆる側面が重要であると思います。

質問内容:

・サイバーセキュリティアドバイザー(情報通信技術を利用したスパイ活動)の質問。治安の有無が幸福にどの程度影響するか。

ジャンの回答:

・安全な環境やコミュニティが生活満足度や幸福感に強く関連するという研究結果があり、安心感はポジティブな影響を与える。

・幸福度報告書では戦争の影響も考慮され、不安定な状況では幸福感が低下することが観察される。

リチャードの追加コメント:

・安全性には多くの次元があり、例えば食料、暴力、拘束、家族関係の安全性などが考慮されるべき。

・マズローの欲求ピラミッドにおいても、安全性は多岐にわたる

チャールズ:その質問に対する感謝を述べます。オンラインでの質問者、ステファニー・キル・オンラインさんは尋ねています。

「子どもと思春期の幸福感について、どう考えていますか? 幸福感の低い子どもは幸福感の低い大人になるのでしょうか? これについてもっと詳しく調査すべきでしょうか?」

ジャン:私たちはそれをより詳しく調べて投資する必要があります。そして、あなたはこれをあなたの本の中で扱っていますが、2つの回答があるとしたら最初の回答は……これは本来リチャードさんが答えるべきことですが、数年前にプリンストン大学出版局から発売された「Well-Being Over the Life Course(人生の経過におけるウェルビーイング)」という素晴らしい本があります。これをチェックしてみてください。

それがまさにその質問に答えており、子どもとその母親に焦点を当てており、出生前からの関係ととても初期の段階での幸福感の重要性、そして人生を通じてどれだけ予測的で重要かを掘り下げています。

それは素晴らしい作品です。現在、私たちは次の世界幸福度報告書を公開するためにウェルビーイング・リサーチセンターのチームと協力して取り組んでいます。実際、人々が参照する世界幸福度報告書は、技術的には18歳以上を対象としたギャラップの世論調査に基づいています。したがって、3月20日に公開される今年の世界幸福度報告書では世代ごとにデータをさらに詳細に分析し、15歳のデータや他の場所のデータ、11、12歳の子供の世界のデータなど、さまざまなデータセットを結びつけることが目的です。

私たちがそこで見ていることは、まだ公表できないのですが、それは直感と一致するものであり、きれいではありませんが、いくつかのことは半ば驚くべきものもあります。ですので、子どもと思春期のウェルビーイングにはもっと焦点を当てる必要があります。データが不足しているだけでなく、特に西洋の世界ではデータがあまり芳しくないからです。子どもと思春期のウェルビーイングは下がり、本当に急落しています。

チャールズ:ありがとうございます。今度は後ろの方に行って…

リチャード:人生の経過における研究には、「しかし」があるでしょうか? つまり、その本で最も重要なたった一つの発見は、子どもを16歳で取り上げ、彼らが幸福な大人になるかどうかを予測したい場合、博士課程まで含めても彼らの単一のテストスコアは、感情の健康のアンケートテストのパフォーマンスよりも幸福な大人になるかどうかを予測するのに悪い予測因子であるということです。

満足のいく人生にとって感情の健康が第一です。たぶん、私は教育省の誰かが来てくれたら私は話せると思います。

質問内容:

・サイバーセキュリティアドバイザーの質問。治安の有無が幸福にどの程度影響するか。

ジャンの回答:

・安全な環境やコミュニティが生活満足度や幸福感に強く関連するという研究結果があり、安心感はポジティブな影響を与える。

・幸福度報告書では戦争の影響も考慮され、不安定な状況では幸福感が低下することが観察される。

リチャードの追加コメント:

・安全性には多くの次元があり、例えば食料、暴力、拘束、家族関係の安全性などが考慮されるべき。

・マズローの欲求ピラミッドにおいても、安全性は多岐にわたる。

──ありがとうございます。本当に興味深かったです。質問があります。

Q. 初めに示したスライドで、スカンディナビアと中央アフリカ共和国の間の違いが示されました。低所得国、特にグローバル・サウスの最も貧しい国々でウェルビーイングに関する議論はどれだけ進んでいるのでしょうか?

チャールズ:理解できましたでしょうか、リチャード?ルーシーはこれらの概念が低所得国、つまり世界で最も貧しい国々でどれだけ話されているかを尋ねました。

リチャード:これは非常に良い質問です。正確に答えることができるかはわかりません。答えます。私が知っている国の中で、ウェルビーイングについて多く話されているのは、中国とインドです。がっかりすることに、それについて話している人はほとんどいません。それはヒンドゥー教の根本的な概念であると考えるかもしれませんが、現代的な議論が生まれていません。私たちは、ギャラップ・ワールド・ポールでそれを研究しています。それはすべての国であり、驚くべきことは、発展途上国でのウェルビーイングの方程式は非常に似ています。

対数収入の幸福への影響は、豊かな国と貧しい国でほぼ同じです。私たちの国では、収入以外にも重要な要因がたくさんあります。例えば、発展途上国におけるメンタルヘルスのひどい軽視は、とても衝撃的です。西洋の開発専門家は、富んでいるか貧しいかに関係なくメンタルヘルスが非常に重要なことだと指摘するために、ほとんど何もしていないと思います。

質問内容:

・スライドで示されたスカンディナビアと中央アフリカ共和国の間のウェルビーイングの違いについて、低所得国、特にグローバル・サウスの最も貧しい国々でのウェルビーイングに関する議論の進捗について尋ねられた。

リチャードの回答:

・低所得国においてもウェルビーイングについての議論は進んでおり、中国やインドが注目されている。

・発展途上国でのウェルビーイングの方程式は、豊かな国と同様に様々な要因が影響しており、例えばメンタルヘルスの軽視が指摘されている。

チャールズ:これに関連する質問として、ライン上のニン・アルウィンさんの質問です。

Q. これはわずかに技術的な質問ですが、これらの比較を行う際の最下位5カ国からのデータの信頼性はどれほどですか?なぜなら、それを集めるのは非常に難しいはずだからです。

ジャン:我々はここでギャラップに多くの義務があり、彼らは代表的なサンプルを収集するために努力しており、スーダン、中央アフリカ共和国、ウクライナなどの紛争地域にまで足を運んでいます。そして、我々は彼らを信頼しており、これらの数値の内的および外的妥当性が信頼できると見ています。

もちろん、国を比較する際には言語の違い、心理社会的または文化的な違い、具体的な項目は何か、それがどのように翻訳され、解釈されるかなどの問題があります。しかし、ある意味で、中央アフリカ共和国などとスカンディナビアの国々との大きな違いがあると思います。アフガニスタンやこれらの戦禍のある国々でのウェルビーイングの低下を見ると、それ自体があなたに直感的なレベルでデータの優れていることを伝えます。

質問内容:

・技術的な質問。最下位5カ国のデータ信頼性について尋ねられた。

ジャンの回答:

・ギャラップが代表的なサンプルを収集し、紛争地域にも足を運んで信頼性を確保している。

・言語、文化、翻訳の違いなどの問題があるが、大きな違いがある国々ではウェルビーイングの低下が直感的にわかる。

チャールズ:ありがとうございます。残念ながら、もう1つの質問の時間しかありません。クララ、選ぶのはあなたにお任せします。

──ありがとうございます。アレックス・マードック、私は引退した教授です。スカンディナビア周辺に住んでいた場所で覚えていることの1つです。

スカンディナビアで気づくことの一つは、一般的な平等感です。人々は他の国ほど所有物や車に高い価値を置いていません。ランキングで全ての国がトップに位置しているのはそのためではないかと思いました。スカンディナビアには「ヤンテ・ロウヴェン」と呼ばれるものがあり、それは「あなたは他の誰よりも優れているわけではない。所有物は特に印象的ではない」というものです。あなたはスカンディナビア諸国におけるこれをどう感じていますか?

リチャード:人間の心理の根本的な問題の一つは、他人と自分を比較する傾向があることです。特にアメリカでは、これはほぼ標準に昇華され、他の人と比較すべきだというのがほぼ規範になっています。人生の仕事はより良くすることであるということになっています。

しかし、その結果、それはゼロサムゲームになります。どれだけ頑張っても、一人の勝者には一人の敗者がいます。

他の人よりも優れようとするならば、より幸福な社会を築くことはできません。ですから、スカンディナビアでは他の先進国よりも多少そのような社会で、他の人と異なることを示そうとするのでなく、他の人と共通のものを活用しようとすることが求められている社会があるとすれば、それは幸福な社会になるでしょう。

質問内容:

・スカンディナビアでは、所有物や成功への焦点が低く、平等感が強い。これがランキングでの高評価につながっているのか。

リチャードの回答:

・アメリカでは他人との比較が標準化され、競争が強調されている。

・他人との比較による競争はゼロサムゲームであり、一人の勝者と一人の敗者が生まれる。

・スカンディナビアの社会では他者との差異よりも共通点を重視し、競争よりも協力が重視される。その結果、幸福な社会が築かれると考えられる。

チャールズ:ここで終了します。質問ではなくコメントとして扱いますが、非常に興味深いものだと思います。ミシェル・ウィルソンさんがオンラインで述べたところによれば、

あなたのデータのリストラで観察された影響を考えると、固定期間の契約と高等教育の不安定性にはどのような類似点があり、教訓はあるでしょうか?

これは大学に向けたメッセージだと思います(笑)。おそらく、後でボトルを開ける時間まで続けることができたでしょう。講演者に感謝する前に、さらに質問があるのは、いつも優れたセミナーの証です。

2月後半に予定している2つの講演について触れましたが、ウェブサイトをご覧ください。1つは完全に異なるトピックではないですが、不平等の問題についての本を出版している民間事業・貿易委員会の労働党委員長リアム・バーンによるもので、それについて話す予定です。そして、おそらく同じ週に、政府主席科学顧問パトリック・ヴァランス卿が登場します。パンデミックの選挙中に頻繁な露出が多かったので皆さんも知っているでしょう。実際には共同体ではなく、科学と政府のより広範な問題について話します。

来ていただき、素晴らしい観客の皆さん、ありがとうございました。私と一緒に、リチャードさんとジャンさんに大きな拍手をお願いします。(👏)

👏👏👏

科学者が政策に参加すること、その深遠な哲学に感動しました。これまで科学に無関心だったことが残念でしたが、今は学びに興奮しています。研究者の知識欲と意志の大切さ、意志の持つ力を理解し、また科学とイラストの組み合わせが効果的な伝達手段であることに感激しました。

(個人的な)考察ポイント:

1. 個人の価値観と感覚を計測する指標の重要性への理解

2. リストラの影響と生活の質の低下のデータに対する興味

3. 社会的・感情的知性の重要性とその成功との関連

4. 良い職場の心地よさと、才能の長期的な保持

5. 低い出発点を持つ人を上へ引き上げることの重要性

6. 他者の幸福向上と費やすエネルギーに関する考察

7. 貧富に関わらずメンタルヘルスの重要性についての認識

8. 他人との比較が生む問題と、弊害についての洞察

後半は難しい部分もありましたが、特にマズローのピラミッドに基づいたお話に深く感銘を受けました。安全の多様な次元についての議論は、自分のウェルビーイングがどのように損なわれるかについて理解を深めました。

また、リチャード先生、チャールズ先生、ジャン先生の3人の関係性がとても和やかで、笑いや気遣いが場のウェルビーイングに寄与していたことが感じられました。チャールズ先生のジョークを通じて、物事にはトレードオフがあることを強く肝に命じました。

ウェルビーイングの科学が、数学、哲学、心理学、行動科学、政治学…など多様な学問が混ざり合ったものだと理解し、改めて研究者への畏敬の念が芽生えました。このような研究を通じて、私たちに示してくれたことに心から感謝します🙏

English(英語):

☑︎ The content of this discussion is based on the video released by the Oxford Martin School. It does not guarantee accuracy or completeness. There is a possibility of misunderstandings or errors in transcription. Please be aware of this in advance.

1. The Flow of the Dialogue(Charles Godfray)

Hello everyone, it’s great to see so many people here. My name is Charles Godfrey, and I’m the director of the Oxford Martin School. It’s with great pleasure that I’m welcoming Lord Richard Layard and Jan Emanuel Den to talk about well-being science and policy. I’ll briefly introduce our two speakers, and then they’ll discuss their new book, which I thoroughly recommend as an extremely accessible summary of the science of well-being. Afterward, the three of us will have a conversation, ensuring there’s plenty of time for questions, and we’ll finish on time at half-past 1.

Lord Richard Layard is a labor economist based at the London School of Economics, where he’s the program director of the Center for Economic Performance, co-founded in 1990. Richard has been influential in public policy for many decades, especially during the Blair-Brown Administration. As a member of the British Academy, he’s received numerous awards, including becoming a life peer in 1990.

Jan Emanuel is from the home side, working at the Said Business School. He grew up in Belgium, attended Harvard University and the LSSE. Together with Richard, he’s been involved in initiatives like the World Happiness Report and co-founded the World Well-Being Movement. He’s actively engaged in policy, including with the Belgium government. With no more ado, Richard, could I ask you to come up? Thank you.

2. Prof Richard Layard

Well, thank you all so much for coming. It’s excellent for our well-being to have you here, and it’s sold out. Some of our colleagues weren’t able to get in, which is a good thing.

I want to start with the first page of our book, and it’s one of 18 illustrations by Mr. Shrigley, a leading designer. It strikes the right note, emphasizing the need for a new world where people experience higher well-being. We’ll only achieve that if we accept it as the objective.

The first point I want to make this morning is we have to agree on the objective; otherwise, we won’t get there. We must agree that the well-being of the people is the overarching objective. Thomas Jefferson put it well: “The care of human life and happiness is the only legitimate object of good government.” Governments exist to improve the well-being of the people and the quality of their lives. Another crucial point is that we want happiness to be fairly distributed. Modern utilitarians aim to combine well-being as the overarching objective with an interest in distribution, ensuring as few people as possible with lower well-being experience misery.

The theory we’re putting forward is that governments must create conditions that enable people to be happier, especially those who would otherwise be in misery. Now, let’s move on to some empirics: who are the people in misery, and how do we identify the causes of the huge spread of well-being in the world? This brings us to the second point: measurement. We can measure well-being, and this has been the revolution of the last 40 years, simply by asking them.

Uh, so this is a question that most of us favor overall: How satisfied are you with your life nowadays, with 0 meaning not at all and 10 meaning very? This is the question used in the official Office of the National Statistics survey annually, and it’s the national statistic of Britain. It’s now recommended by the OECD to all its member countries. It has many merits; it’s simple, easy to understand, much better than the common practice in some places where they have lots of questions and then create an index by applying some weights. This is also more democratic than having researchers applying weights; the person themselves applies the weights to what matters to them and how they feel about it.

We know that this question has strong information content; it’s a very good predictor of how long you will live, just about as good as a medical diagnosis. It’s a good predictor of whether you’ll leave your job or your partner. Yan will be explaining more about whether you will vote for the incumbent government, which is, of course, why policymakers should take it especially seriously.

So let’s look at some basic facts which this question reveals about The Human Condition, which I know the Martin School is focused on. This is the distribution of well-being in the world. You can see it’s extraordinarily unequal, with a fifth at three or below and the sixth at eight or above. Part of that spread, of course, comes from the variation between countries, and part of it comes from the variation within countries. Let me take them in that order.

The top countries tend to be Nordic; they tend to be peaceful, egalitarian, and the bottom ones tend to be those torn by civil conflict or repression. But, of course, other factors come in, which explain the differences across countries, including income but also health, freedom, social support, altruism, trust—all variables where the Nordic countries do well. In fact, in the famous wallet-dropping experiment, 80% of the wallets dropped in Nordic countries were returned, compared with half in our country and the US, and under 20% in China.

Even though there are these big differences between countries, actually, 80% of the variation in happiness in the world is within countries, including our own. So let’s move on to what explains the spread within countries because if we want to know how to reduce misery, we’ve got to know what’s causing the spread because that’s the same factors as causing the lower tail. Here’s the answer to that—many, many causes. And, of course, income is a very poor proxy, as you will see from the next slide.

This slide I’m putting up is a result of estimating an equation across a survey where you’re having to explain the life satisfaction of each individual by as many factors as you can find that explain it. In this graph, we’re going to show the impact of each variable in terms of its explanatory power to explain life satisfaction and the variation of it holding each other factor constant. You’ll see that the biggest factor is mental health, defined as the answer to the question:

Have you ever been diagnosed for an anxiety disorder or depression? Physical health, perhaps not so well measured, is also important. Family life is very important, and employment, of course, and the quality of work, including relationships. And then income.

But this is what you get from running a regression of life satisfaction on these variables. But another way of getting the importance of these variables is, of course, just to ask people what they worry about in their daily life. Remarkably, the answers are almost exactly the same ranking as you see there. This is such a different picture from what most politicians and most journalists think are the sources or the things that matter to people in their lives. It’s really important that we get a new perspective based on this paradigm.

The position of income here helps to explain the fact that in many countries, growth has not been accompanied by rising happiness.

The USA is the most obvious one for which we have the longest time series, pretty much flat, actually declining a bit toward the end. So there’s no time obviously here to discuss the huge volume of research, which establishes proper causal estimates of the effect of different factors on well-being. All spelled out in our book, and we think that this body of knowledge is now strong enough for the fourth and final proposition. Oh, sorry, I jumped.

The proposition is that policymakers should judge policies by how much they increase well-being per pound being spent. This is what the OECD and the EU have been asking their member countries to do, and of course, it’s wonderful that KSTA has made this remark.

With every pound spent on your behalf, we’d expect the treasury to weigh not just its effect on national income but also its effect on well-being. Stimulated by that, about half a dozen of us at LLC are busy trying to show how that can be done. And to those of you who are economists, let me just stress, we’re not throwing away traditional cost-benefit analysis. Willingness to pay can still be used where there’s enough evidence from revealed preference. But there are many other effects of policy that can’t be picked up through revealed preference, and these have to be evaluated using self-reported well-being. And then you can combine the two because you know what is the marginal utility of income. So using this method, we’re able to cover huge areas of life where traditional cost-benefit analysis wasn’t possible. And these analyses, of course, will then imply major new priorities. I mentioned mental health, obviously, child well-being, youth apprenticeship. I’m very keen on family conflict, elderly care. These things are as important as the more obvious things for increasing income. So it’s really time that we had a broad criterion of well-being to evaluate the whole of public spending. It would be wonderful if the Martin School would take an initiative in doing this because I think it’s perfectly placed to provide a leader, a lead in this way of analyzing public policy. Yan will be explaining to you why that’s also in the interest of the politicians. So I have no doubt that in the years to come, well-being will become the objective of government, at least in this country. And since it’s more than 200 years since we Jefferson and Benam advocated this, it’s surely time. Thank you. [👏]

3. Prof Jan-Emmanuel De Neve

Thank you, Richard. Thank you, Charles. Thank you, everyone, for the great privilege and the opportunity to present our work and our book to you. I’ll build on Richard and highlight a few of the insights that we develop in the book. I’ll start with building on the important point that Richard just made. Besides arguably a moral imperative to put well-being much closer to the heart of policymaking, we also now have evidence that it’s not just the right thing to do but probably also the politically astute thing to do.

Advances here are made by our former student, now dear colleague George Ward, who in a very important paper in our view in the American Journal of Political Science four years ago published this work where he trailed through all of the European elections and looked at variation in incumbent vote shares and linked that to variation in well-being, that measure that Richard has introduced to you,

as well as compared this to the traditional classic economic voting time variables, which are obviously GDP growth rates, employment or unemployment, and inflation.

What George found, and why I think this is such an important piece of work, is that well-being, subjective well-being, well-being as people rate the quality of their lives themselves, is a better predictor of incumbent vote share than any of the other more economic items are. The more you let that sink in, and I do advise you to read that paper, you’ll see it’s actually quite intuitive because voting is while you’re taking in the objective world around you, you do so through a subjective lens. And for that reason, I think our subjective well-being measures actually come quite close to that truth as people experience it.

Besides being the politically astute thing to do, it’s also probably the politically necessary thing to do in certain situations. What you’re seeing here is an analysis we did for the book,

which is the March 15th, 2019, Hong Kong protests were high on the political agenda or the media agenda. So we looked at GDP as a predictor of potential unrest and then compared that with how that might be different when you look at well-being as a predictor of social unrest in these cases. And what you’ll see is Hong Kong, if you had just looked at the economic data in this case, GDP per capita, what an extraordinarily good news story this was. In the space of just shy of a decade, they’ve increased GDP per capita by about 50%. If,

however, you look at how people actually feel in Hong Kong and, in particular, in this case, the youth and the younger generation, you would have seen that there was a drop, a significant drop in how people rated the quality of life as they experience it. This also mirrors our analysis of this kind that looked at the run-up to the Arab Spring, where we’ve got the inspiration for this analysis. But it shows you that there’s something very powerful that subjective well-being, well-being matters, bring to the table that traditional GDP indicators do not.

Alright, let me turn to the world of work, which has been mostly my focus of research. And Richard already highlighted the fact that workplaces are an important driver of global general well-being. But just how important is it really? And here too, well-being science has made a lot of advances and I think can really add to labor economics and thinking more broadly about the importance of work. We all know work is important, and it’s because of both the paycheck, the income it provides, but beyond that, the non-pecuniary elements to do with social status, identity, social networks, routine throughout the day, and so much more.

What we’re showing here is what it does to one’s well-being if all of this is taken away. So what you’re seeing here is a time cohort study where you see people before being made redundant and following being made redundant. Obviously, the word “making redundant” should probably be refrained, and it’s not the word that you shouldn’t be using in these instances.

But it is obviously describing what happens. What you’re seeing here is a drop, if you put gender together, of about one point on a scale from 0 to 10 when people are being made redundant. That is a lot, especially because typically people in average populations are six, six and a half, seven in the case of the UK. So losing a whole point, in the case of males even more, you’ll find that there’s close to a 20% drop in well-being and quality of life as you experience it. That is huge and it’s obviously one of the key insights and most probably one of the most robust insights that have come out of well-being science and have really added to labor economics, I think.

There is a small difference between men and women, but I think the main instinct coming through following the importance of work for well-being is also the fact that people don’t adapt to unemployment. So typically in well-being science, we found that whenever a shock to life happens, whether positive or negative, people tend to adapt to it relatively quickly, even things that you wouldn’t expect people to adapt to. But not so for losing their job, and again, I think mostly for the non-pecuniary reasons just highlighted in labor economics. This now has a term that has been coined for this, which is the scarring effect of unemployment. This type of science, these types of results, I think put even more pressure on policymakers, especially on the economics front, to try and do as well as they can to maintain people in work and do a good job for them, both the quantity and quality of jobs.

Alright, that is work for the importance of work for well-being, but can we turn this around?

How important is how we feel at work for the quality of our work, our individual performance if you will, and possibly even organizational performance? That’s what we’ve spent quite a bit of time working on in recent years, and I’m very pleased to share with you a paper that was published last year in Management Science that took us about seven, eight years to produce, and I think it produces the first causal field evidence for the link between how we feel as individuals and how that translates into our performance, literally in this case from one week to another.

We studied BT call center employees one week to another, pulsing how they felt from one week to another every Thursday at 4 p.m., to be more precise, and then linked that to incredibly granular performance data—weekly sales, customer satisfaction, number of seconds on a call, how many calls, you name it. What you’re seeing here is the main, we can talk about this for an hour, but what you’re seeing here is the headline result, which is essentially if you feel much better than you did the previous week, we find up to about 12-133% increases in weekly sales. It’s very tangible.

Now, interestingly, and this is just a side note, but it also depends on the kinds of tasks you’re doing, the importance of how you feel. So what this is is just an average effect. When people were asked to deal with, say, disgruntled customers, retaining their business, the importance of how they felt from one week to another was way more important than this. On the other hand, admittedly, when it was just order taking, where no social and emotional intelligence was required, there was little or no effect of how you felt. So it goes to show, for anybody working in a workplace well-being and is involved with workplaces more generally, the degree to which you’re applying social emotional intelligence is very much and the success of that is very much driven by how you feel it yourself in the first place. And we picked this up in a way that’s never been shown before.

Now, this is at the individual level, and this starts hinting at the fact that if there’s such strong powerful links at the individual level between how we feel and the quality of our work, does that feed into larger organizations? This is one channel by way this might go. There’s other channels. A good workplace where people feel good is probably going to be attracting more talent because people have word of mouth and other places to find out whether it’s a good workplace. A good workplace where people feel good is probably going to retain their talent for longer as well. And so all these channels and pathways, can we then show whether there’s also a link at the organizational level? And I’m very pleased to say in the last two years, we’ve done a lot of work on that.

What you’re seeing here is the results of the world’s largest study on workplace well-being, where in this case, we’ve got more than 1,600 US-listed firms where we have both solid well-being data crowdsourced.

Um, thanks to platforms like Glassdoor and Indeed linked to the quarterly data that these companies need to provide in a systematic, comparable way. What you’re seeing here is bins with the top 10%, the bottom 10%, and everything in between. What you’re seeing is the average company well-being coming back to us from the employees themselves through our crowdsource measures is very strongly associated with the key financial performance metrics, whether it’s gross profitability, return on assets, or firm value. This is obviously just contemporaneous, these are associations or correlations, but there’s definitely something very powerful between how we feel at work as an organization and how that translates into organizational performance.

Can we go a step further and see whether there’s sort of predictive power? One way of doing that is to look at stock markets. What you’re seeing here is an analysis that got a lot of attention in the media and is something very basic; it’s called a portfolio analysis. Anybody investing in stocks, you’ll be familiar with this. Think of it as follows: say you’ve got $1,000 to invest. Most of you might do this in an index fund, such as the S&P 500. What you would have been given back if your $1,000 over the last few years since we have the data would have been something somewhat positive, despite a lot of volatility.

So what you’re seeing here is 2021, 2022, in the start of 2023 with the traditional benchmark indices going up, going down, and then volatility in 2023 so far. What we’ve done is we’ve looked at the extraordinary data we’ve got on how people feel in these listed companies, put them in an index—take the top 100, you can take the top 200 or top 50, whatever you want—and then see whether that outperforms on the stock market.

What you’re seeing here now is something really rather extraordinary. It shows that the stock market doesn’t fully value the intangibles of how people feel, and part of it is because they don’t necessarily have access to the data on this. But even if they did, they seem to underestimate the importance of how workers feel and how that, over time, feeds into the bottom line.

Just a reminder, what we’ve done here is the 2020 data on workplace well-being, put that in an index, and let that run starting January 1st, 2021, and then do the same thing again at the start of 2022 and the same again at the start of 2023. A portfolio based just on quality workplaces would have outperformed all the major indices.

Now, if this doesn’t convince you or little interest, hopefully, the stuff that Richard shared with you is of interest, and if failing that, we’d suggest that you still have a look at the book because there are extraordinary illustrations by David Shrigley in there that are really peak one’s thinking.

So, I’ll leave it at that, put the main screen back on, and thank you very much for your time. [👏]

4. Q & A

Charles Godfray:So, um, I’m going to start with a question.

Q. So, um, I’m going to start with a question. There will be an election this year; we’re non-party political at the Martin School, so we don’t know if it’s going to be Starmer or Sunak or Farage. But if you got the phone call a few days after the election, we have no money, what can we do that would make a difference to people’s lives that we could do relatively fast?

Lord Layard:Well, I’ve got actually three things. First, I want this policy oriented to well-being, and I want to change altogether what goes on in Whitehall so that’s how people think about policy priorities for any government.

My next thing, as you say, there’s no money. I’ve got some policies which don’t actually save money, more save more money than they cost. I was involved in developing what’s now called NHS talking therapies for anxiety disorders and depression, and we’ve been able to show that that saves more money in terms of getting people off disability benefits into work, paying taxes, also saving NHS money on physical health care, far in excess of the original cost.

I want now a parallel service for addiction and personality disorders, which are causing havoc in our society and in our families. More difficult to treat, but on the other hand, the savings will be even greater. So that’s my second thing.

My third thing is I think it’s an absolute disgrace in this country how we treat people after they leave school if they don’t go to university. We have no proper system of vocational training and apprenticeship, which is as easy to access as the university is if you go down the academic route. It’s a disgrace. I want guaranteed access to apprenticeship.

De Neve:Great. I’ll add something in the sense that the science does show that mental health workplaces, all the policy items that Richard has just highlighted are incredibly important. I think there’s a third one, and I’ll actually paraphrase something that Richard is known for: the social infrastructure. So you’ve got the actual infrastructure. Politicians are always very keen to invest in roads, HS2, trains, what have you, and that needs to be done, but not at the expense of or by overlooking social infrastructure.

Social capital, social trust, things that we’ve lost in many cases turn out to be a lot more important than people think at different levels of life. For example, in our World Happiness Report, when you look at what explains variation between countries, then a lot of things play a role, including income, of course, but the one that stands out as the strongest tends to be social support, social capital, volunteering opportunities, trust in each other, trust in institutions. So I think there’s a lot more work there to be done, and it tends to be overlooked because it doesn’t necessarily feed into GDP.

Charles Godfray:So let me ask you a couple of questions about people who have sort of challenged the well-being approach.

Q. You mentioned that you described yourself as a new utilitarian, and utilitarianism has had a mixed ride over the last century. There are many schools of thought associated with rights, associated with capabilities and things who feel who I suspect would be very happy with many of your microanalyses but would be worried about an overarching utilitarian framework worrying that it will affect the rights of disadvantages. I know you address some of this in the book, and I wonder if you might just elaborate a little bit more on what you mean by being a new, a modern utilitarian.

Lord Layard:Jeremy Bentham suggested that the objective should be simply the sum of happiness or the average of happiness in the population. I think most modern people with this type of approach, but I have to exclude Peter Singer, who’s a very distinguished utilitarian at Princeton, but apart from him, I think most people feel that it must be more important to enable somebody starting low to move up by one unit of happiness than to do the same for somebody starting high. So this, I think, leads to the way we would, within this framework, express the idea of social justice.

The idea of social justice is that priority is to be given to people who are starting low. But then we need, of course, this much wider concept of starting low than simply income. Maybe you want to come back to that later, but that’s my concept of utilitarianism applied in a way that’s sensitive to the distribution of well-being as well as its average.

Charles Godfray:But I guess the advantage of economic utilitarianism is you have a metric there, money, which is sort of you don’t argue with.

Q. But taking this more sophisticated approach, how do you actually define the function that allows you to weigh the interests of people with different backgrounds or different status?

Lord Layard:This, of course, is a problem because the views that people have on this differ, and it’s a normative and an ethical question. We’re talking about how can academics help policymakers to achieve what they value. So I can write down, of course, a mathematical value with a sort of parameter which values as to how egalitarian the policymaker is. But another way, obviously, more straightforward way for policymakers who are not mathematically minded is to print out what is the impact of your policy on people who are starting at different levels of well-being and look at different policies and let policymakers make their choice using their own judgment.

Charles Godfray:Thanks so much, Yan. Could I ask you a question?

Q. So there has been some criticism from the left of the approach. People from the left are often very happy about shifting from finance to thinking about well-being but then worry about some of the analyses might underestimate the role of income distribution. So some of the things that you put up there that were correlated with happiness might actually mask the underlying effect of income and distribution. And I have heard people say, well, a problem with well-being, it may mask some of the entrenched power relationships in the economy that sort of maintain the status quo.

De Neve:It’s a difficult question.

I think first and foremost, I would be surprised by that criticism coming from the left because in a way, well-being and the main result has really been diminishing marginal utility of income itself. If you look at it from an economics perspective, it really suits a center-left agenda on progressive taxes and redistribution because what we found very clearly is somebody making a million, the extra 10,000 will mean less in terms of subjective well-being than somebody making 10,000 getting an additional 10,000. That’s been pretty well established, and so it gives you a whole new angle or perspective or justification for progressive taxation that is not typically used. Um, so I think that helps that part of the agenda.

Now, there’s also the well-being agenda can also help on the conservative side, and so which is why it’s so exciting because it’s something in an agenda that left and right, Center can find themselves in. Yes, of course, GDP or income could sit behind some of the elements. For example, if education has a positive impact on well-being, it may well be because of the socioeconomic status and the power and wealth that sits behind some of that. But in the science when you dig into the book, you’ll see we do try and look for causal inference, which would take out these omitted variables that might be hiding in the shadows.

So income matters, I don’t think anybody should be naive about that, but there are diminishing marginal utility. And for me, as somebody with in economics, it always blows my mind that one of the first things you learn is diminishing marginal utility of hamburgers, of Coca-Cola, of anything you consume, but it’s very rarely applied in economics 101 to income itself. And we find that so clearly, and so I think that is probably a big insight coming through for the left.

Charles Godfray:Thank you, Richard. I’m a biologist, so clearly Aristotle is a hero man, and I felt at the beginning of the book that you were a bit down on Aristotle and his ideas of eudemonia and The Virtuous life. But then Amar sort of came back a bit later on when you talked about the importance of not just a sum of individual well-being but societal well-being as well.

Q. And is there a role for thinking about what makes a virtuous life in not only increasing your own happiness but the happiness of society more broadly?

Lord Layard:What you just said at the end, of course, is true, but the question is what is the objective. The great thing about Aristotle, of course, was that he had this idea that there must be if you were to have a certain coherent way of thinking about what you’re trying to do, you can only have one objective which you use to compare the value of different courses of action.

So I mean, he, the Telos, this is a great idea in Aristotle. And the problem with Aristotle is that he then defined as the objective something which was a mixture of good experience and virtue. Whereas this doesn’t quite resolve the issue. We would think of virtue as a means to the end of a society in which people are enjoying their lives. But obviously, a society in which people enjoying their lives won’t exist if people are each only concerned with promoting their own well-being.

So a means to a society in which people are enjoying their lives is that people devote a lot of their energy to improving the well-being of other people. So virtue is a means to the end.

De Neve:It also, of course, is to some extent has rewarding effects on the person, the virtuous person, but virtue is mainly to be advocated because it produces a good overall outcome for everybody.

And if I may comment on that, I think that the key here is what Richard just said at the end: virtue is its own reward, to some extent, and there’s now wonderful proof of this, work done with NHS volunteers showing that obviously it helps people they’re helping, but it also helps them to some extent. So if we do put well-being as the ultimate criterion to inform policy, and that sort of encapsulates virtues behaviors as well.

So if I were to clone myself right now and I do something nice for another person, and my other clone, my clone, does something bad for another individual, the version of me that has done something good pro-socially should feel better, should have higher life satisfaction. And so that, I think, is something that will help provide weight behind having a measure like life satisfaction at the very top because it incorporates virtuous behaviors to some extent, maybe not fully, but to some extent.

Charles Godfray:Might I ask you a question about well-being over time? And you showed that astonishing results about how well-being now can affect voting preferences, and that if, as a politician, then that would really reinforce you need a budget give-away just before an election. So presumably, what you want is a measure of well-being that sort of takes into account the trade-offs of doing that to the future.

And then in the book, you talk about climate change as well, which is the sort of mother of all trade-offs in the future. And you argue that with well-being, then you take a similar approach to economics, but your discounting value is lower, so you value the future more.

I guess I have two questions. So if you look at the economic literature,

Q. it’s slightly scary how much the policy implications depend on assumptions about discount rates, sort of Nordhaus versus Stern, for example. So how do you, the problem is the future is so big that sort of basis points change in the discount rates make a huge difference. How do you get around some of those problems?

Lord Layard:The basic concept of the discount rate, which is used by economists, say by the treasury, is there’s an element of what you call pure time preference, connected with uncertainty. They have one and a half percent. And then there’s the assumption that as people become richer with economic growth, their marginal utility of income will be lower, so it’s not so important to give them the higher income. The treasury has it at 2%. So that gives you 3 and a half percent, which I think means that in the year 2100, a pound then is worth to us today six pence. So you can forget the end of the century. And this is what The Economist who were against the climate change movement relied on. What was hopeless about it, in a sense, was thinking about the whole thing in terms of income because income is not the only thing that matters to people.

If their whole society is turned upside down and they’re on the move and they’re all kinds of other people being disrupted by their arrival, etc., etc. If you think in terms of well-being, then you are left only with the one and a half percent, which gives you a much more serious approach to future generations.

I mean, when we talk about whose well-being matters, I think we would like to say that the well-being of future generations matters as much as our own. But then you get into a logical problem because everything is valued at infinity. So you’ve got to have an element of discounting, but it shouldn’t certainly be too high.

De Neve:IBut it does make a big difference, exactly. Richard put it beautifully that if you take well-being seriously and put it at the heart of policymaking, it also helps you deal with climate change and environmental challenges because, as Richard said, you don’t want to discount the well-being of future generations by nowhere near as much as the economic approaches would. Richard is quite right. In traditional economic approaches, currently baked into the UK government’s cost-benefit analysis is 3 and a half to 4%. So, that means, in what is it, 75 years from now, we don’t look very much beyond 2100 in that case, whereas we would, of course, when we think about future generations and their well-being.

Charles Godfray:I’m about to go to the audience, but I have one last question, which is partly facetious but partly serious.

Q1. So, I plan this evening to open a nice bottle of red wine, and I suspect my well-being will sort of incrementally go up. Is that a virtuous thing to do?

Q2. And the serious question is the criticism you bring up in the book, the famous Aldous Huxley “Brave New World,” where if we were to come up with a drug that increased our subjective well-being, and it tends to go against an Aristotelian virtuous life, one does it by cheating. How do you confront the Aldous Huxley “Soma” question?

Lord Layard:I think the first thing that I would say is, what would happen actually if somebody invented a drug that made you feel better than you otherwise would, with no side effects? I mean, why wouldn’t we all take it? I mean, we organize our lives in all kinds of ways to make our lives enjoyable—what we eat, different foods. What’s wrong with including a pill? I just don’t see anything wrong in that at all. I think he was absolutely barking up the wrong tree there.

De Neve:I guess the key is if there are no tradeoffs. So, for something that feels wonderful, there may still be tradeoffs. If you didn’t go to work at all, and I think your bottle of red wine is a perfect example. In moderation, it might help, but in too much, it will have negative spillover effects on the next day.

Charles Godfray:I have some experimental data to support…

Thank you for your question. Let me go to the audience. Just remind everyone we are being recorded, so just beware that will happen. Would someone like to put up their hands? If you could, in the front here, Clara, and if you can just wait for the microphone to come, my hearing is not that great. I’ll just check. Yeah, it’s fine.

──I’m a great fan of everything you’re doing. I work in the field of emotional intelligence, but I’ve got two points which I’d like to hear your comments on.

Q. We’re talking about science and policy. In order to create policy, you need to have a criterion to judge against. You mentioned the ultimate criterion, and in all the graphs and things I’ve seen, happiness, life satisfaction, and well-being seem to have been interchanged. In fact, one had life satisfaction across the bottom and happiness, that was a US one along the bottom. Others had well-being everywhere, and I feel that it’s not particularly helpful unless you’re going to define each one because they seem to be interchangeable. Now, with the new data that exists, I was part of the 2007, forgive me, we have lots of questions, you happiness conference, and we’ve got much more data now. So that’s my first thing, that we need to be clear about.

Lord Layard:I’m going to stop you there. The book is mainly about life satisfaction, which is the concept used in the World Happiness Report and the most used and most researched definition. That, as you know, is what people call evaluative well-being, sort of involves an element of judgment about how you feel about your life. What language is difficult here, but how you feel about your life is not quite the same as how you feel at the moment. That’s what’s called hedonic, as you know. To measure how people feel over the integral of time is obviously a massive research task, for a start.

There are a lot of problems, I think, in having that as your ultimate maxim. For example, do you include dreams? All kinds of issues to do with consciousness and so on. I think we’re at the early stages in this subject. It’s been going in this form for at most 40 years, and I think, for the moment, particularly in the realm of policy, policymakers are very used now to asking people how satisfied are you with your police service or your transport system. Why not just jack it up to how satisfied are you with your whole life?

Charles Godfray:Thank you. I know there’s lots of expertise in the room, but please could you keep your questions short so we hear from the speakers? Then I’ll go to one from online. I’ll keep it short and sharp.

──I’m ex-military. I advise in cyber intelligence, and I’m also a mentor for a military charity. In my career, I have seen horrors, and certainly in cybersecurity, there are some pretty awful things happening to people. In such a short period, you’ve really got me thinking because security is so important to people’s lives.

Q. But to me, and I’m probably wrong, it appears that a lack of security is negative (look at Gaza, Ukraine), but positive security is neutral. And I just wonder if there is evidence that well-being can be experienced by people who simply are living secure lives.

De Neve:That is a tough question. Thank you for your service and for your question. Security is fundamental to well-being. There is a substantial body of research that indicates a strong connection between a sense of security and well-being. People who feel secure in their homes, communities, and broader environments tend to report higher levels of life satisfaction and well-being. This extends beyond physical security to include economic and social security as well. When individuals feel secure in various aspects of their lives, it positively influences their overall well-being. However, the relationship is complex, and different individuals may weigh the importance of security differently based on their experiences and perspectives.

Um, I think you’re quite right. Sometimes we get the criticism saying the World Happiness Report that some country doesn’t move much until there’s a war, of course, and then boom, way down. So you’ll see in the World Happiness Report that we’re preparing now, we actually dig into the Israel-Gaza-Ukraine data a bit more, as we already did Ukraine last year as well. So you see huge drops in the case of insecurity, and it certainly really hits home. Afghanistan, actually, before that, what happened two years ago was bad; now it’s at the very bottom. The average reported life satisfaction of Afghanistan is not even two out of 10. That’s the average, which means that if one person says five, that means you need another 10 to put it in zero. So insecurity is hugely damaging, but I think you’re quite right. Once there’s sort of a secure base, then people, Rich is going to hate me for saying this, but Maslow’s Pyramid of Needs, then they start thinking possibly about other things. But there are questions about Maslow’s hierarchy of needs.

I’m going to ask a question. Can I just, I mean, you mentioned Maslow, your question about security is a good one because think of all the dimensions of security. There’s food security, there’s security from violence, there’s security from imprisonment, the security in your family relationship, is your wife going to betray you, the security for your, are your children doing all right? So I think it’s, there’s even insecurity.

Lord Layard:Do you feel your place in the universe is okay? So I just want to say that there is no evidence, nor was any produced by Maslow, in favor of the Maslow hierarchy. All the good research done by Ed Diner, who’s the founder of this subject, showed that these effects are additive, but of course, all dimensions of security matter.

Charles Godfray:Thank you for that question. Stephanie Kill online asks,

“What are your thoughts regarding child and adolescent well-being? Do children with low well-being become adults with low well-being? Should we be looking at that more closely and investing?”

And you do deal with this in your book, but perhaps you might, do you, Richard, if I?

De Neve:There’s two, um, two answers. The first one is, and this is really, should be Richard answering, is he’s got an amazing [book] came out with Princeton University Press a few years ago called “Well-Being over the Life Course,” which, for whomever the person is online, check it out because that’s precisely it. They’re digging into the best data sets that have looked at kids and their mothers even before birth and those relationships and the importance of well-being at those very, very early stages and how predictive and how important that is as you go through life.

Um, so it’s a brilliant piece of work. Now, I do want to—I get excited about this question because we’re working on it right now with the team at the Well-Being Research Center for the next World Happiness Report we are publishing. And I, um, the world, the biggest piece of research trying to tie in all the data sets worldwide around child and adolescent well-being. Because, truth be told, our World Happiness Report that people tend to refer to is based off the Gallup World Poll, these rankings, which is technically 18 plus. And so, for this year’s World Happiness Report, which will come out on March 20th, the aim is precisely to start slicing and dicing this a bit more between generations and dragging the pool of data, which is 15-year-olds and data from elsewhere, children’s worlds with 11, 12-year-olds, data from not the entire world but lots of places, including some of the global South.

What we’re seeing there, um, I can’t yet reveal because it’s embargoed, but it’s something that aligns with intuition, which is not pretty, as we all know, but some things are also semi-surprising. And so, there needs to be a lot more focus on child and adolescent well-being, not just because there’s little data—we need more focus, but also because the data isn’t looking pretty, especially in the Western world. It’s coming down, and it’s really falling off a cliff.

Thank you. I’m going to go to the back now for—

Lord Layard:Is there a butt in that study of the life course? I mean, the most important single finding in that book, um, is that if you take a child at 16 and you want to predict whether they will be a happy adult, their exam scores, even right up to their Ph.D., are a worse predictor of whether they’ll be a happy adult than just performance on a single test score, um, questionnaire test of emotional health. So, yeah, emotional health is number one for a satisfying life. I think I can spot Lucy if only was someone here from the Department of Education.

──Thank you. That was really fascinating. I was curious, um,

Q. when you put out an early slide showed differences between Scandinavia and the Central African Republic, and I was just wondering, what is the discourse? How far has the discourse on well-being gone in the kind of lowest-income countries in the global South?

Charles Godfray:Did you get that, Richard? No? Um, so Lucy asked how much of these concepts are talked about in low-income countries, the poorest countries in the world. It’s a very good question. I’m not sure I can answer it correctly.

Lord Layard:Um, I can. The countries which I’m aware of where it’s talked about a lot are China, um, India—disappointingly, as it seems to be, we’ve hardly located anybody talking about it. Although in some sense, you would think it was a fundamental Hindu concept, but it hasn’t generated a sort of modern-type debate. But, um, I mean, we have studied it, of course, in the Gallup World Poll. It’s every country, and what’s remarkable is that the well-being equation is very similar in developing countries.

The effect of log income on happiness is pretty much the same in rich and poor countries. There are so many other factors as well as income, which are important, and I think, for example, the awful neglect of mental health in developing countries is absolutely shocking. And development specialists from the West, I think, have done very little to point out that mental health is an incredibly important thing, whether however rich or however poor you are.

Charles Godfray:A related question to that, Nin Alwin on the line, and this is slightly more technical one:

Q. How good is the data from the bottom five countries when you were making those comparisons? Because it must be very hard to collect.

De Neve:We owe a lot to Gallup here, and they go out of their way to try and have a comparable approach to collecting a representative sample of countries, and they even go into places of conflict, from Sudan, Central African Republic, Ukraine. And so we do trust them, and we see the internal and the external validity of these numbers seem reliable.

Now, there are obviously questions about when you start comparing countries—language differences, psychosocial or cultural differences, what is the specific item, how does it translate, how is it interpreted—so there are differences. But I think, in a way, the big differences you see between, say, Central African Republic, as was raised, and the Scandinavian countries, that in and of itself gives you—I mean, people, when you see these drops in Afghanistan or in these war-torn countries, that speaks for the data from a very good, instinctive level, I think.

Charles Godfray:Um, when you see these drops, thank you. We have time for one more question, I’m afraid, Clara. I’ll let you choose.

──Thank you, and thank you for the walk from the station. Uh, Alex Murdoch here. I’m a retired professor, particularly around Scandinavia where I’ve lived. One of the things that I note with Scandinavia is a general sense of equality.